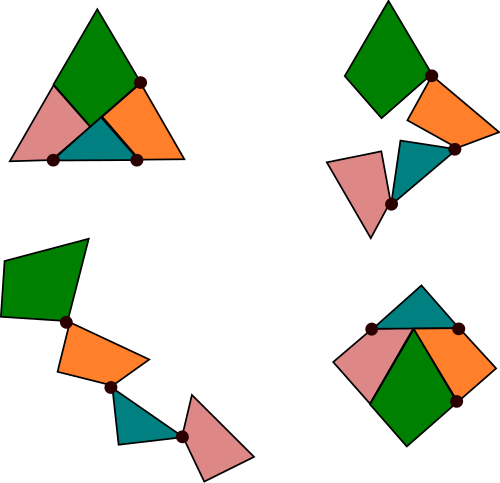

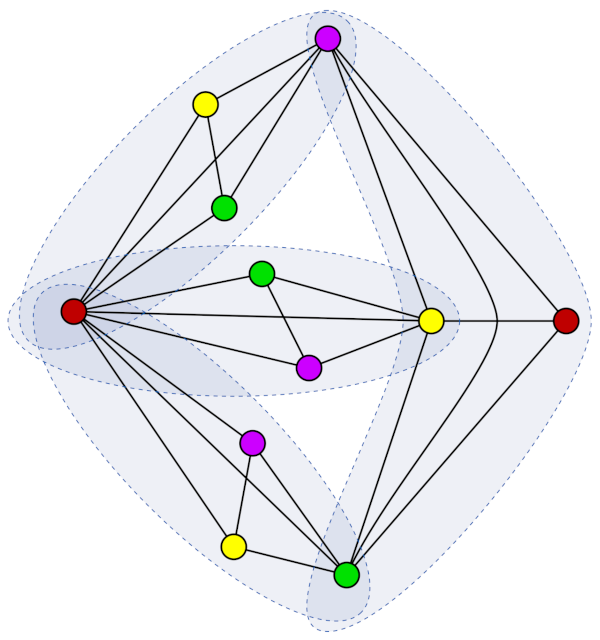

This figure contains four “cliques” of four points each, with each of the four points in each clique connected to each of the others, and each pair of cliques intersecting at a single point. Four colors suffice to color all the points so that no two linked points share a color.

Is this always possible? If k cliques, each containing k points, are arranged in similar fashion, can the result always be colored properly with k colors? In 2021, half a century after Paul Erdős first posed the question, Dong Yeap Kang and his colleagues proved that, for sufficiently large k, the conjecture is true.