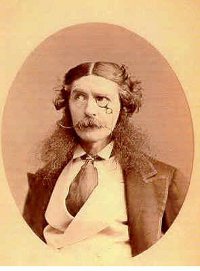

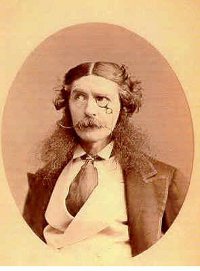

When a visiting Englishman expressed disappointment that New York had revealed none of the bohemian color that he had hoped for, actor (and inveterate joker) Edward Sothern invited him to a dinner for twelve.

While the soup was being served, one man laid a battleax beside his plate, another a knife, and others produced guns, scythes, and staves.

“For heaven’s sake,” whispered the Englishman, “what does this mean?”

“Keep quiet,” replied Sothern, “It is just what I most feared. These gentlemen have been drinking, and they have quarrelled about a friend of theirs, a Mr. Weymyss Jobson, quite an eminent scholar, and a very estimable gentleman, but I hope for our sakes they will not attempt to settle their quarrel here.”

At that one guest leapt to his feet and cried, “Whoever says that the History of the French Revolution, written by my friend, David Weymyss Jobson, is not as good a book in every respect as that written by Tom Carlyle on the same subject, is a liar and a thief, and if there is any fool present who desires to take it up, I am his man!”

In the ensuing melee, someone thrust a knife into the Englishman’s hand and said, “Defend yourself! This is butchery — sheer butchery!”

Sothern sat by and said only, “Keep cool — and don’t get shot.”

Sothern was famous for such jokes; it’s said that few of his friends attended his funeral because they assumed the announcement was a hoax. Once, at a restaurant, he and a friend gathered up all the silverware and hid under the table. Outraged, the waiter ran off to summon the police. When he returned, the two were sitting at their places as if nothing had happened.