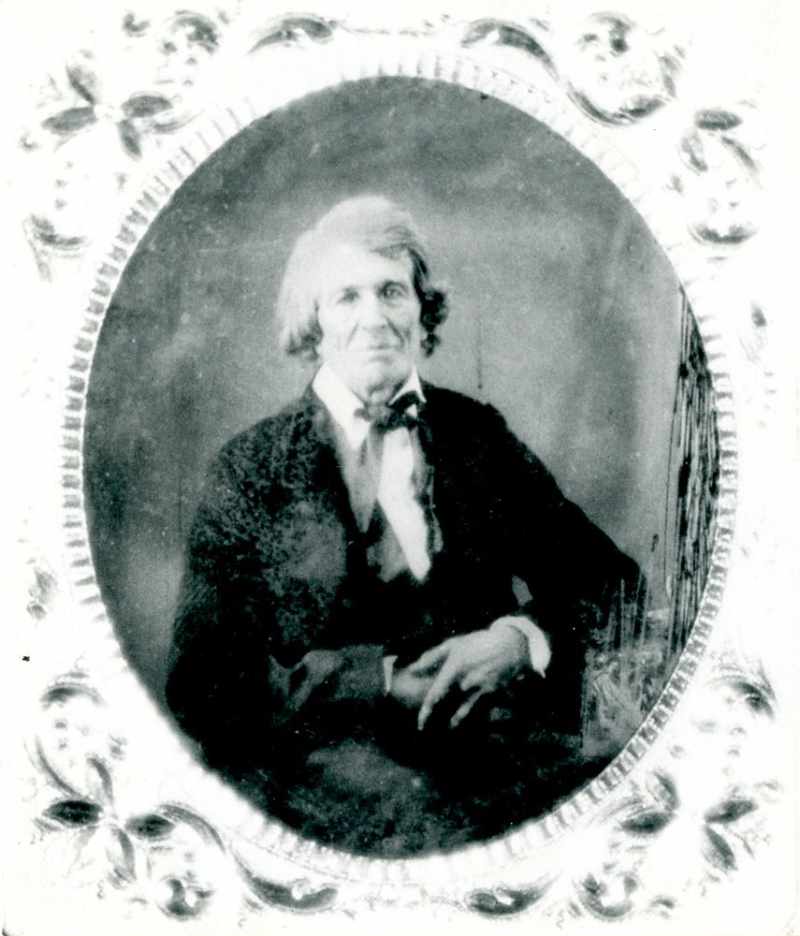

John Owen, one of the last veterans of the French and Indian War, lived to be 107 and posed for this photograph shortly before his death in 1843.

That makes him one of the earliest-born humans ever to be photographed. He was born in 1735.

John Owen, one of the last veterans of the French and Indian War, lived to be 107 and posed for this photograph shortly before his death in 1843.

That makes him one of the earliest-born humans ever to be photographed. He was born in 1735.

What’s the sum of all the digits used in writing out all the numbers from one to a billion?

“I always feel an optimist when I emerge from a tunnel.” — Robert Lynd

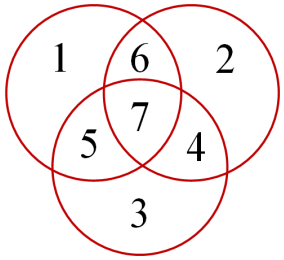

The numbers 1-7 are disposed among the regions in this figure such that each of the circular sets yields the same sum. This makes it a “magic Venn diagram,” a concept that occurred to mathematician David Robinson while teaching a course in mathematical logic at the University of West Georgia. His article appears in the December 2025 issue of Recreational Mathematics Magazine.

(David Robinson and Anja Remshagen, “Magic Venn Diagrams,” Recreational Mathematics Magazine 12:21 [December 2025], 25-44.)

I do not object to being bored if I am paid for it, but I never am paid for it. So many people have run up such long scores with me in this respect, and never paid me, that I will give no more credit. I must have cash down before I will be bored at all, but my figure is very low; so long as I get paid at all I will give people as much fun for their money, by way of letting them bore me, as anyone is likely to do.

— Samuel Butler, Notebooks, 1912

A conversation in Spoonerian, a language conducted entirely in spoonerisms, proposed by J.A. Lindon:

A: Hot woe, Barley Chinks!

B: Hot woe, Chilly Base!

A: Blocking showy, Miss Thorning.

B: Glowing a bale.

A: It slacked one of my crates.

B: I’ve a late slacking. The drain rips in.

A: Porter on the willows? Tut-tut!

B: Mad for the bite. Cuddles on the pot.

A: A very washy splinter.

B: All blood and mowing.

A: Here’s to spray in the Ming!

B: Sadsome glummer! ‘Ware fell!

A: Low song!

‘John Carter,’ the young English convict whose poems brought him pardon, left a farewell message to his friends within the walls of his Minnesota prison. This ‘last will and testament,’ first printed in the weekly Prison Mirror, published in the penitentiary, was reproduced in The St. Paul Dispatch:

‘This is the last will and testament of me, Anglicus. I hereby give and bequeath my collection of books (amounting to some 6,000 volumes) to Mr. Van D., in memory of the not altogether unpleasant hours we spent together, hours marked by no shadow of animosity at any time. We could not be happy, but we were as happy as we could be. To Dr. Van D. I leave my mantle of originality, and what remains of the veuve cliquot, in memory of encouragement when I most needed it.

‘To the editor I leave my space on this journal and the best of good wishes in memory of his unfailing courtesy and forbearance.

‘To Uncle John and to Sinbad go my heartiest wishes that we may meet soon in some brighter clime.

‘To Mr. Helgrams, my best dhudeen and the light of hope.

‘To young Steady and to Mr. D. M., my poetic laurels, which they are to share in equal measure.

‘To the boys in the printing office, the consolation of not being obliged to set up my excruciating copy.

‘To the tailors (and to the boss tailor in particular, ‘Little Italy,’) my very best pair of pants.

‘To Jim of the laundry, — but nothing seems good enough for Jim, the best soul that ever walked.

‘To Porfiro Alexio Gonzolio, a grip of the hand.

‘To Davie, pie, pie again, and yet more pie.

‘To the band boys — why, here’s to ’em! May they blow loose.

‘To my fellow pedagogues, “More light,” as Goethe put it, more fellowship; it would be impossible to wise them. They know where I stand and I know where they stand.

‘Lawdy! lawdy! If I hadn’t forgotten Otto and his assistant. Here’s all kinds of luck to ’em, and no mistake about it.

‘Finally to all those not included hereinbefore (for various reasons), here’s to our next merry meeting. To those in authority, thanks for a square deal. To mine enemy — but I mustn’t bul-con him.

‘Gentlemen, I go, but I leave, I hope I leave my reputation behind me.

‘Anglicus.’

— New York Times, July 9, 1910

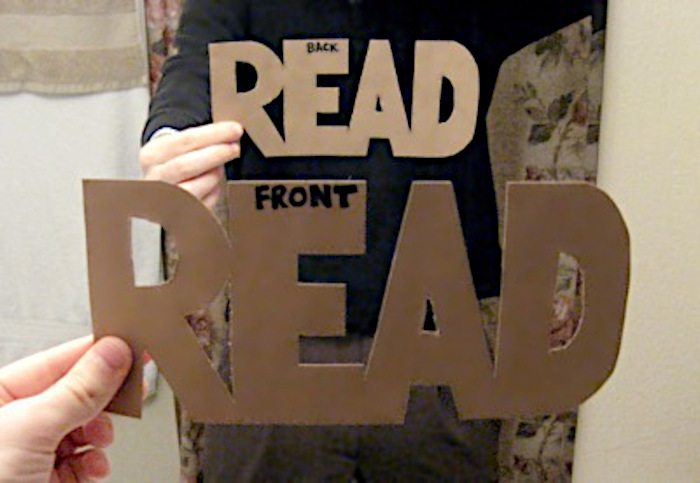

We tend to think that mirrors reverse left to right, but in fact they reverse “back to front,” along an axis perpendicular to the mirror’s surface. Our confusion arises when we misinterpret this.

“[I]magine a back-front reversal of yourself, with your nose, face, eyes, and so forth pushed through to the back of the head, and your back somehow oozed through to the front,” writes University of Auckland psychologist Michael C. Corballis. “You might then ‘feel’ your watch as having remained on the left wrist (say), while back and front have reversed. However it is likely that you will also experience a strong compulsion to recalibrate your internal axes, and then feel the watch to be on the right wrist. In short, a back-front reversal is reinterpreted as a left-right reversal.”

(Michael C. Corballis, “Much Ado About Mirrors,” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 7:1 [2000], 163-169. More mirror puzzles.)

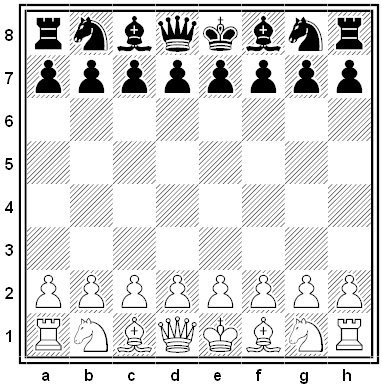

In an 1890 cable match with Mikhail Chigorin, Wilhelm Steinitz played a Two Knights’ Defense in which his king knight found its way from g1 to f3, g5, h3, and g1 again in the first 13 moves. Beside himself, Siegbert Tarrasch wrote this satirical account of a game played 30 years hence, in 1920:

1. Nf3

Introduced by Zukertort, in honour of whom the opening is named. But as the latter never hit upon the correct continuation, it is better known at the present as the Four Knights’ game.

1. … Nf6

Zukertort’s opponents used to play 1. … d5, showing but a superficial knowledge of the true science of chess by moving Pawns which they could not retract. The text move is the only correct one.

2. Nc3

An excellent move, demonstrating powers of deep strategy. A novice might be tempted to play 2. d4 instead of the text. It cannot, however, be sufficiently impressed upon the mind of the student that a Pawn when once moved cannot be retracted, and that it forms a target for attack from the adversary’s pieces.

2. … Nc6

The second player also displays great generalship.

3. Ng1

A masterly conception! Threatening to obtain considerable advantage by also retiring the other Knight, and thereby preventing his pieces from being molested by hostile pawns for a long time.

3. … Ng8

Perceiving the danger at the right moment, this manoeuvre leads to at least an even position.

4. Nb1! Nb8!!

The spectator sees — doubtless with admiration — two masters of the highest rank thoroughly acquainted with all the most subtle points connected with the game of chess. Both sides are guarding against creating weak spots by pushing Pawns rashly. In former days experts used to move these Pawns for the purpose of developing pieces. But as early as the end of the last century it became more and more obvious that this is a mistake, for if once moved they may be attacked by hostile pieces, and even captured if not properly taken care of.

5. Nh3

An ingenious attempt to gain an advantage in another way. That the Knights are better placed here than in the centre of the board where they command too many squares was equally well known at the end of the last century.

5. … Na6!!

6. Na3!!! Nh6!!!!It would be difficult to imagine play on either side more precise or more accurate and entirely in accordance with the accepted rules laid down by the masters of the present day.

7. Ng1 Ng8

Both of these moves were originated by the greatest master of the last century, who played them in a celebrated correspondence match. He was the only chess-player of his time who had penetrated so deeply into the theory of the game. He was considered the father of modern chess.

8. Nb1

At this stage Black offered a draw. White has a momentary advantage in having a piece less developed than his opponent. But this, perhaps, is not sufficient to win. The draw was therefore agreed upon.

(Via the British Chess Magazine, March 1891.)

It’s been known since 1882 that it’s impossible to construct a square with the area of a given circle using only a compass and straightedge.

But in 1977 Thomas Elsner showed that the task becomes possible if the circle is allowed to roll: