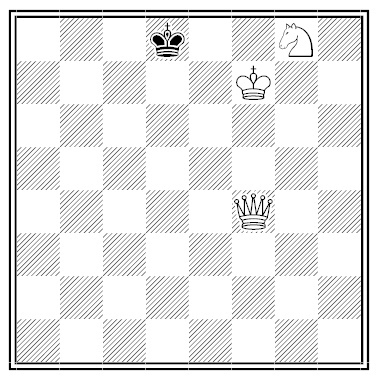

By Eric Angelini, Europe Echecs, 1990.

White adds one square at the edge of the board and then mates in two.

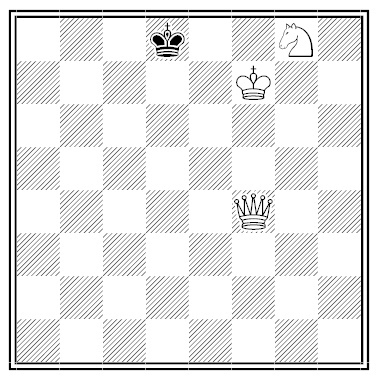

By Eric Angelini, Europe Echecs, 1990.

White adds one square at the edge of the board and then mates in two.

ALL FOR ONE AND ONE FOR ALL is a word-level palindrome.

So is the witches’ chant FAIR IS FOUL, AND FOUL IS FAIR in Macbeth.

Irritated with Britain’s repeated “paper blockades” of the American coast, privateer Thomas Boyle slipped into the English Channel in 1814 and proclaimed a one-ship blockade of the entire United Kingdom:

Whereas it has become customary with the Admirals of Great Britain, commanding small forces on the coast of the United States, particularly Sir John Borlaise Warren and Sir Alexander Cochrane, to declare all the coast of the United States in a state of strict and rigorous blockade, without possessing the power to justify such a declaration, or stationing an adequate force to maintain said blockade, I do therefore, by virtue of the power and authority in me vested (possessing sufficient force) declare all the ports, harbors, bays, creeks, rivers, inlets, outlets, islands, and seacoast of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, in a state of strict and rigorous blockade. And I do further declare, that I consider the force under my command adequate to maintain strictly, rigorously, and effectually, the said blockade. And I do hereby require the respective officers, whether captains, commanders, or commanding officers, under my command, employed or to be employed on the coasts of England, Ireland, and Scotland, to pay strict attention to the execution of this my proclamation. And I do hereby caution and forbid the ships and vessels of all and every nation, in amity and peace with the United States, from entering or attempting to enter, or from coming or attempting to come out of any of the said ports, bays, creeks, rivers, inlets, outlets, islands, or seacoasts, under any pretence whatsoever. And that no person may plead ignorance of this my proclamation, I have ordered the same to be made public in England.

The proclamation was posted in Lloyd’s Coffee House in London — and, back home, won his ship the title “The Pride of Baltimore.”

More maxims of Rochefoucauld:

And “Why have we memory sufficient to retain the minutest circumstances that have happened to us; and yet not enough to remember how often we have related them to the same person?”

But how are we to figure the change from ‘undecided’ to ‘true’? Is it sudden or gradual? At what moment does the statement ‘it will rain tomorrow’ begin to be true? When the first drop falls to the ground? And supposing that it will not rain, when will the statement begin to be false? Just at the end of the day, 12 p.m. sharp? … We wouldn’t know how to answer these questions; this is due not to any particular ignorance or stupidity on our part but to the fact that something has gone wrong with the way the words ‘true’ and ‘false’ are applied here.

— F. Waismann, “How I See Philosophy,” in H.D. Lewis, ed., Contemporary British Philosophy, 1956

Crocheting Adventures With Hyperbolic Planes has won the 2009 Diagram Prize for Oddest Book Title of the Year, with 42 percent of the vote. Other contenders:

The winning book informs readers how to “crochet models of the hyperbolic plane, pseudosphere, and catenoid/helicoids” and explores geometry and the history of crochet. “It defended its poll-topping position despite strong support for the spoon-carrying Third Reich, once again attempting to muscle in on someone else’s territory,” said prize custodian Horace Bent. “But the public proclivity towards non-Euclidean needlework proved too great for the Third Reich to overcome. If only someone had let the Poles know in ’39.”

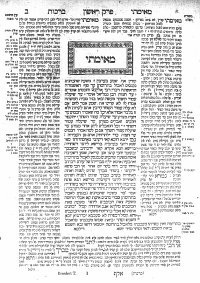

Writing in Psychological Review in 1917, Berkeley psychologist George Stratton reported the startling achievements of Jewish scholars known as Shass Pollaks, who would memorize the entire Babylonian Talmud — not just the text, but the position of every word on every page:

“A pin would be placed on a word, let us say, the fourth word in line eight; the memory sharp would then be asked what word is in the same spot on page thirty-eight or fifty or any other page; the pin would be pressed through the volume until it reached page thirty eight or page fifty or any other page designated; the memory sharp would then mention the word and it was found invariably correct. He had visualized in his brain the whole Talmud; in other words, the pages of the Talmud were photographed on his brain. It was one of the most stupendous feats of memory I have ever witnessed and there was no fake about it.”

Stratton also quotes Judge Mayer Sulzberger of Philadelphia, who had seen a Shass Pollak put down a pencil at random in the Talmud and immediately name the word on which it had lighted.

These achievements, Stratton wrote, “should be stored among the data long and still richly gathering for the study of extraordinary feats of memory.”