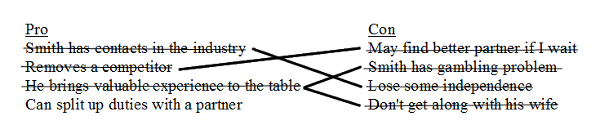

In a 1772 letter to Joseph Priestley, Ben Franklin described a method “for arriving at decisions in doubtful cases.” He would divide a sheet of paper into two columns, labeled Pro and Con, and during the course of three or four days record all the motives for and against the idea. Then he’d assign a weight to each consideration. Where he could find arguments, sometimes in combination, that counterbalanced one another, he would strike them out:

Should I enter into business with Mr. Smith?

(This example is from Paul C. Pasles, Benjamin Franklin’s Numbers, 2008.) This exercise would show him where the balance lay, and if after a day or two of further reflection no additional considerations occurred to him, he would come to a decision.

“Though the weight of reasons cannot be taken with the precision of algebraic quantities, yet, when each is thus considered separately and comparatively, and the whole lies before me, I think I can judge better, and am less liable to make a rash step; and in fact I have found great advantage from this kind of equation, in what may be called moral or prudential algebra.”