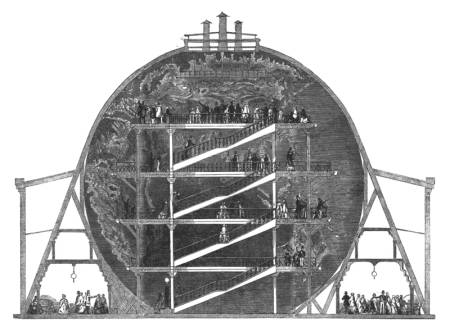

Mapmaker James Wyld gave London an enormous gift in 1851 — a 60-foot globe fitted with an internal staircase from which visitors could view the surface of the world, complete with rivers and mountains sculpted in plaster. More than a million guests filed through the exhibit in 1851, which promised “the whole extent, figure, magnitude, and multifarious features of the world we live in, as if it were one vast plain.”

“It has been suggested to us that the interior should be fitted up as lodgings for foreigners,” Punch enthused. “By this arrangement a foreigner would feel himself perfectly at home, though really abroad.”

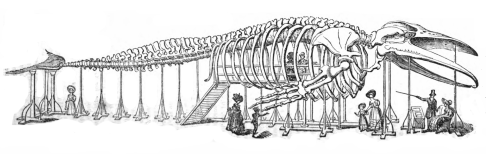

In the same spirit, in 1831 the skeleton of a 95-foot bowhead whale was displayed in a pavilion at Charing Cross, as part of a tour that had also touched Ostend and Paris. Visitors could ascend a flight of steps to a stage set within the ribcage, where they could sit at a table and write puns in the guest book. (“Why should we be mourned for if killed by the falling of the bones of the whale? We should be be-wailed.”) Jokers called the pavilion “the palace of the Prince of Whales.”