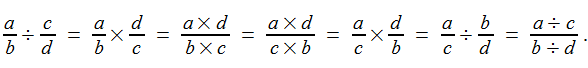

In 1983 a driver hit a tree in Michigan. A tree surgeon repaired the damage, and the driver’s insurance paid the $550 bill, but the tree’s owner claimed $15,000 for pain and suffering; he said the “beautiful oak” was like someone dear to him.

A lower court threw out the case, and the appeals court agreed. The three-judge panel declared:

We thought that we would never see

A suit to compensate a tree,

A suit whose claim in tort is prest

Upon a mangled tree’s behest;

A tree whose battered trunk was prest

Against a Chevy’s crumpled crest;

A tree that faces each new day

With bark and limb in disarray;

A tree that may forever bear

A lasting need for tender care.

Flora lovers though we three,

We must uphold the court’s decree.

Affirmed.

(Fisher v. Lowe, 122 Mich. App. 418, 33 N.W.2d 67)