He killed the noble Mudjokivis.

Of the skin he made him mittens,

Made them with the fur side inside,

Made them with the skin side outside.

He, to get the warm side inside,

Put the inside skin side outside;

He, to get the cold side outside,

Put the warm side fur side inside.

That’s why he put the fur side inside,

Why he put the skin side outside,

Why he turned them inside outside.

— George A. Strong, “The Modern Hiawatha,” in The Home Book of Verse, 1918

Ofttimes when I put on my gloves,

I wonder if I’m sane,

For when I put the right one on,

The right seems to remain

To be put on–that is, ‘t is left;

Yet if the left I don,

The other one is left, and then

I have the right one on.

But still I have the left on right;

The right one, though, is left

To go right on the left right hand

All right, if I am deft.

— Ray Clarke Rose, “Simple English,” in Wallace Rice, A Book of American Humorous Verse, 1903

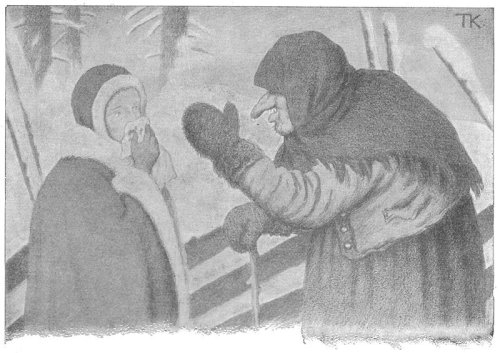

“What can be more similar in every respect and in every part more alike to my hand and to my ear, than their images in a mirror?” wrote Kant in 1783. “And yet I cannot put such a hand as is seen in the glass in the place of its archetype; for if this is a right hand, that in the glass is a left one, and the image or reflection of the right ear is a left one which never can serve as a substitute for the other. There are in this case no internal differences which our understanding could determine by thinking alone. Yet the differences are internal as the senses teach, for, notwithstanding their complete equality and similarity, the left hand cannot be enclosed in the same bounds as the right one (they are not congruent); the glove of one hand cannot be used for the other.”