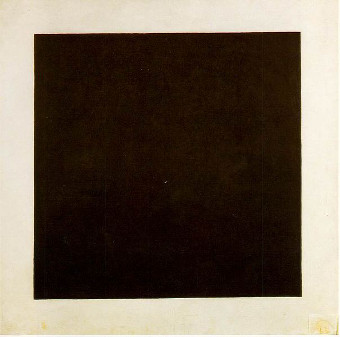

In 2002, Russian magnate Vladimir O. Potanin paid $1 million for Kazimir Malevich’s 1915 painting Black Square. “‘All paintings are pictures’ would have been a strong candidate for a necessary truth until Malevich proved it false,” wrote Arthur Danto of the inscrutable black canvas. Malevich himself had said, “It is not painting; it is something else.”

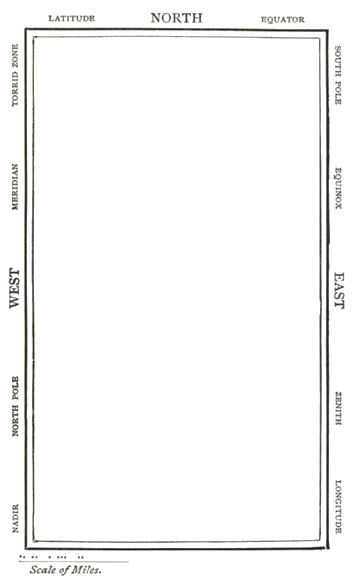

In The Hunting of the Snark, the Bellman guides his party across the Ocean with “a map they could all understand”:

“What’s the good of Mercator’s North Poles and Equators,

Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?”

So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply

“They are merely conventional signs!

“Other maps are such shapes, with their islands and capes!

But we’ve got our brave Captain to thank”

(So the crew would protest) “that he’s bought us the best —

A perfect and absolute blank!”

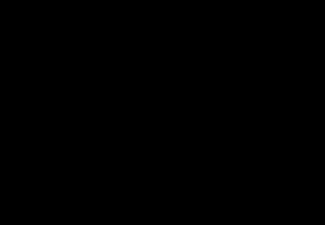

While an architecture student at Cornell in the 1920s, practical joker Hugh Troy was given 48 hours to render “a conception of what a brightly floodlighted hydroelectric plant might look like at night.” “Though Hugh was overloaded with other work, he got his drawing in on time,” remembered classmate Don Hershey. He called it Hydroelectric Plant at Night (Fuse Blown):

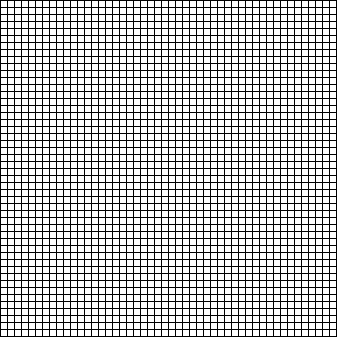

In 1967 British artists Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin produced a “map of itself,” a “map of an area of dimensions 12″ x 12″ indicating 2,304 1/4″ squares”:

Katharine Harmon, in The Map as Art, writes that this is one of a series of maps “revealing only what they wished to show and jettisoning the rest — drawing attention to what cartographers have always done.”

(Thanks, Tristram.)