Confederate officer Tod Carter had been away from home for three years when he found himself crossing into his beloved Tennessee in late 1864 with Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood. As they approached his hometown of Franklin, Carter received permission to pass ahead and visit his family, but he found that Federal forces had commandeered the house to serve as headquarters in the coming battle. Miserably he returned to camp.

On Nov. 30, while Carter’s family and friends cowered in the house’s stone basement, Hood’s forces collided with those of Union general John Schofield. The battle produced 10,000 casualties in five hours; around the house men fought viciously with bayonets, rifle butts, axes, and picks. Carter’s older brother Moscow later wrote, “While the terrible din of the battle lasted it seemed to the adults that they must die of terror if it did not cease, but when there was a lull the suspense of fearful expectation seemed worse than the sound of battle.”

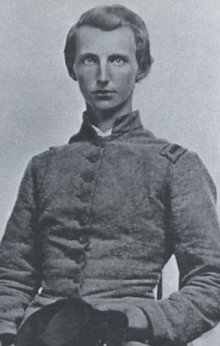

As a quartermaster, Tod might have been spared the danger; his duties did not involve combat. But, wrote Ralph Neal in a company history, “It was on the first charge and when nearest the enemy’s works that Capt. Todd Carter dashed through our lines on his horse with drawn sword, made straight for his father’s house, and met his death as it were, on the very threshold of his parental home. He was perhaps not more than fifty feet from us when he fell; his horse was seen to plunge and we knew he was struck. Captain Carter was thrown straight over the horse’s head, his sword reached as far as his arm would allow toward the enemy, and when he struck the ground he laid still, and his brave young life went out almost at the door of his home.”

“The sight of home and all that makes home dear, and that home in possession of the enemy caused him to forget himself, and under the impulse of the moment he rushed to certain death.”