Schoolteacher George Pocock invented a unique means of transportation in 1826 — the Charvolant, a buggy drawn by kites. By training the kites and turning the carriage’s front wheels, the “charioteer” could steer even along a road at right angles to the wind. “Thus,” he found, “whatever road the car may travel by a side-wind, the same road it may return by the same wind; and where there is space for traverse, as on plains or downs, it is possible to beat up against the wind.”

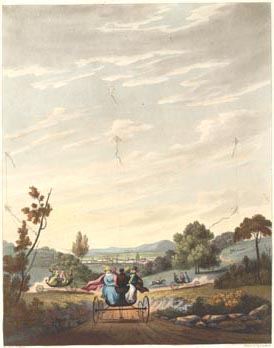

“This mode of travelling is, of all others, the most pleasant,” Pocock wrote in his 1851 Treatise on the Æropleustic Art. “Privileged with harnessing the invincible winds, our celestial tandem playfully transpierces the clouds, and our mystic-moving car swiftly glides along the surface of the scarce-indented earth; while beholders, snatching a glance at the rapid but noiseless expedition, are led to regard the novel scene rather as a vision than a reality.”

In experiments with a four-wheeled car drawn by two kites on leads of 300 yards, Pocock found that a high wind could produce speeds of more than 40 mph; in one friendly race three Charvolants carried 12 passengers 113 miles from Bristol to Marlborough in a single morning. Pocock estimated that a party of six might cross the Sahara in 10 days and 10 hours for a total cost of about £80. “Is it too fond a hope that, by the system of æropleustics, those sands may be navigated as the sea, and thus a most speedy and safe communication be opened between the east and the west of the interior?”

As a side benefit, Pocock found that the Charvolant could travel freely on English turnpikes, which assessed tolls by the number of horses that drew an equipage. “The herald-bugle is sounded — the gates fly open — you pass unquestioned,” Pocock marveled. “Those who travel by Kites travel as kings.”