The hedge maze at Hampton Court has been entertaining visitors since 1695, occasionally belying its reputation for ease. In Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat (1889), Harris says, “We’ll just go in here, so that you can say you’ve been, but it’s very simple. It’s absurd to call it a maze.” Then, after two miles of wandering:

‘The map may be all right enough,’ said one of the party, ‘if you know whereabouts in it we are now.’

Harris didn’t know, and suggested that the best thing to do would be to go back to the entrance, and begin again. For the beginning again part of it there was not much enthusiasm; but with regard to the advisability of going back to the entrance there was complete unanimity, and so they turned, and trailed after Harris again, in the opposite direction. About ten minutes more passed, and then they found themselves in the centre.

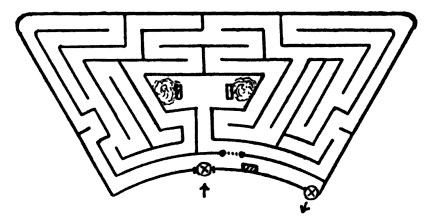

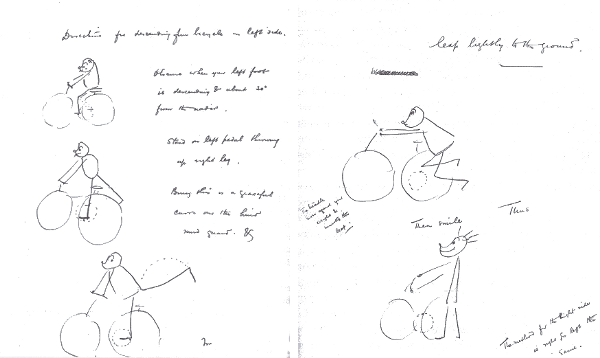

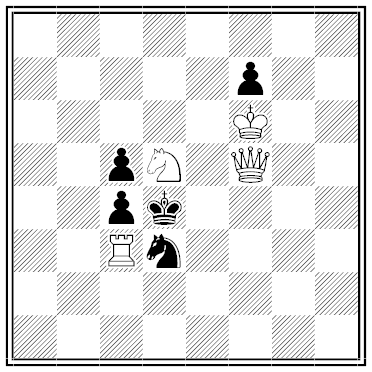

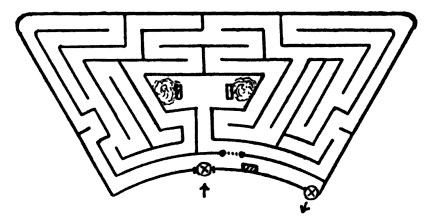

Mazes have exercised a peculiar fascination for the mathematically minded. The young Lewis Carroll composed this one for a family magazine — the object is to make your way from the outside to the central space; it’s acceptable to pass over or under another path, but a single line means your way is blocked.

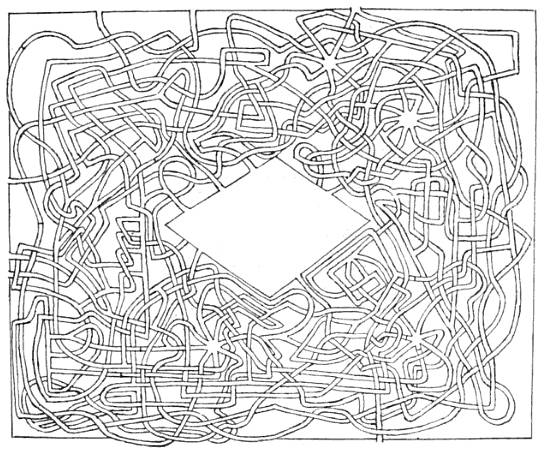

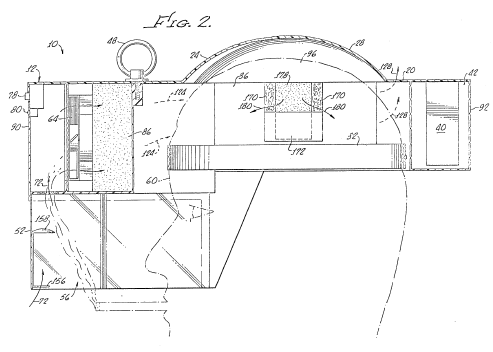

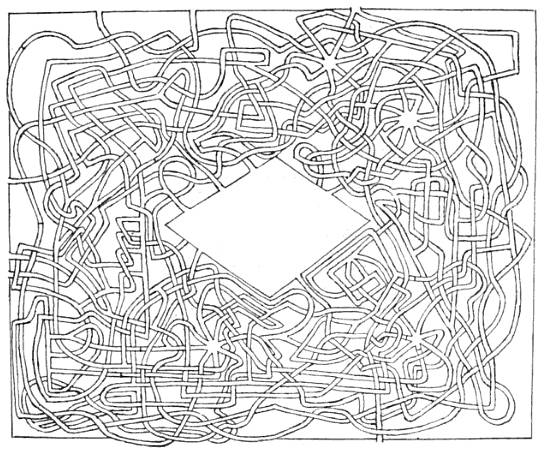

Cambridge University mathematician W.W. Rouse Ball constructed this maze in his garden. He notes that unless a loop surrounds the goal, the wanderer can defeat any maze by trailing one hand along a wall, and “no labyrinth is worthy of the name of a puzzle which can be threaded in this way.”

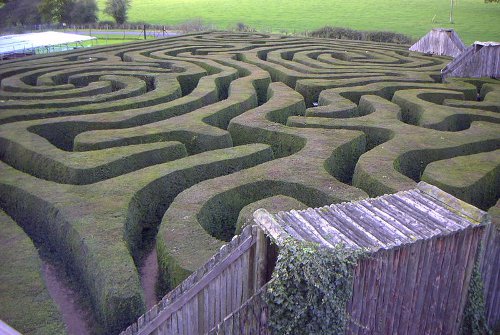

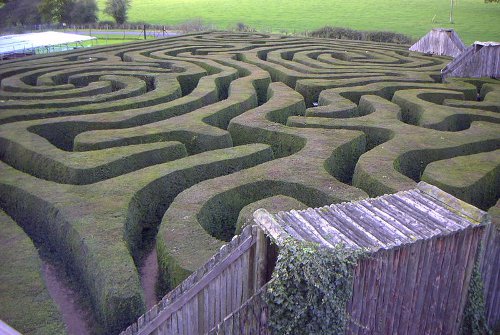

Hampton Court is modest in comparison to the modern hedge maze at Longleat, a stately home in Somerset. Its 16,000 English yews enclose 1.75 miles of paths that require an hour and a half to traverse; the course includes six wooden bridges from which to plot a path to the goal, an observation tower.

In solving any of these, as Harris discovered, the chief danger is overconfidence:

Said a boastful young student from Hayes,

As he entered the Hampton Court maze:

“There’s nothing in it.

I won’t be a minute.”

He’s been missing for forty-one days.

— Frank Richards