In 1891, Robert Baden-Powell wandered the mountains of Dalmatia with a butterfly net and a sketchbook. If he was accosted by one of the forts in the area, he would show his drawings to the soldiers and explain that he was hunting a particular species, and they would send him on his way.

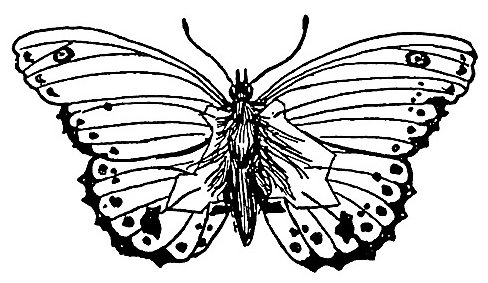

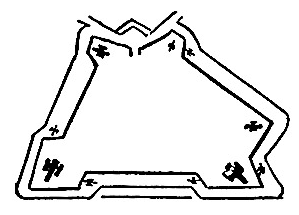

In fact he was working as an intelligence officer for the British government. “They did not look sufficiently closely into the sketches of butterflies to notice that the delicately drawn veins of the wings were exact representations, in plan, of their own fort, and that the spots on the wings denoted the number and position of guns and their different calibres”:

The large dots denote the locations of the fort’s main guns, and the smaller show field artillery and machine-gun emplacements.

“Fortunately for us, we are as a nation considered by the others to be abnormally stupid, therefore easily to be spied upon,” he wrote in his 1915 memoir My Adventures as a Spy. “But it is not always safe to judge entirely by appearances.”