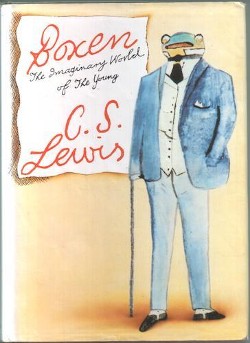

Stuck in a book-filled house in dreary Belfast in 1906, the 8-year-old C.S. Lewis repaired to the attic with his 11-year-old brother Warren and began to fashion an imaginary world. Jack’s half was called Animal-Land, and Warnie’s was an island called India. The two, connected by steamship routes, formed a world they called Boxen, the subject of novels, textbooks, maps, and even newspapers that the two composed over the next five years:

In those days Mouse-land was called ‘Bublish’ and the mice called Bubills.

Shortly after the ‘Melee of Hacom’s Palace’ (for so it shall be called) some inhabitants of Bombay came over to buy nuts. They taught the mice many things. The most important of which was: the use of money. Before that the Mice (or Bubils as they were called) exchanged things in markets. The Indians landed in 1216.

The Indians as it has been told gave knowledge to the Bublis. But the Bublies asked for some of it. The Bublis asked the Indians how they got on without fighting each others men. The asked ones told the Bubils that they choose a man to rule them all and called him Rajah or king.

The Bubils followed that plan. But no!! ‘Out of the frying-pan into the fire.’ Poor miss led creatures. Now they fought all the more!! Why? Because each mouse wished to be king. One had as much right to the throne as an other. So every place was fighting.

Jack’s Animal-Land drew on the “dressed animals” of Beatrix Potter, but, influenced by the political table talk of their father, it set them in prosaic histories and palace intrigues rather than heroic adventures. “For readers of my children’s books, the best way of putting this would be to say that Animal-Land had nothing whatever in common with Narnia except the anthropomorphic beasts,” he wrote later. “Animal-Land, by its whole quality, excluded the least hint of wonder.”