Asked why he was riding naked in the rain, American eccentric Hugh Henry Brackenridge pointed to the clothes folded under his saddle.

“The storm, you know, would spoil the clothes,” he said, “but it couldn’t spoil me.”

Asked why he was riding naked in the rain, American eccentric Hugh Henry Brackenridge pointed to the clothes folded under his saddle.

“The storm, you know, would spoil the clothes,” he said, “but it couldn’t spoil me.”

Excerpts from an Independence Day oration by Nashville attorney Edwin H. Tenney to the Young Men’s Association of Great Bend, Tenn., July 4, 1858:

“What does he mean by ‘blowing up the ramparts of beauty?'” wondered the Daily Alta California. “The obscurity can’t be in the writer, and must therefore lie in our own ignorance. Still we ask — what are the ramparts of beauty?”

“I wrote somewhere once that the third-rate mind was only happy when it was thinking with the majority, the second-rate mind was only happy when it was thinking with the minority, and the first-rate mind was only happy when it was thinking.” — A.A. Milne

Here’s an imaginative newspaper hoax from the American West — James Wickham, a “scientific English gentleman,” was said to have released two 35-foot whales in the Great Salt Lake in 1873:

Mr. Wickham came from London in person to superintend the ‘planting’ of his leviathan pets. He selected a small bay near the mouth of Bear River connected with the main water by a shallow strait half a mile wide. Across this strait he built a wide fence, and inside the pen so formed he turned the whales loose. After a few minutes inactivity they disported themselves in a lively manner, spouting water as in mid-ocean, but as if taking in by instinct or intention the cramped character of their new home, they suddenly made a bee line for deep water and shot through the wire fence as if it had been made of threads. In twenty minutes they were out of sight, and the chagrined Mr. Wickham stood gazing helplessly at the big salt water.

If Great Salt lake were in Asia it would be called a sea. It is seventy-five miles long and from thirty to forty wide, so it is easy to perceive how readily the whales could vanish from sight. Though the enterprising owner was of course, disappointed and doubtful of the results, he left an agent behind him to look after his floating property.

Six months later Mr. Wickham’s representative came upon the whales fifty miles from the bay where they had broken away, and from that time to the present they have been observed at intervals by him and the watermen who ply the lake, spouting and playing.

Within the last few days, however, Mr. Wickham cabled directions to make careful inspection and report the developments, and the agent followed the whales for five successive days and nights, discovering that the original pair are now sixty feet in length, and followed about by a school of several hundred young, varying in length from three to fifteen feet. The scheme is a surprising and complete success, and Mr. Wickham has earned the thanks of mankind.

I’m not sure when it first appeared. The earliest publication I can find is in the Salt Lake Herald of June 27, 1890, which noted that the article was “again going the rounds” and reprinted it “merely to show that while great interest is taken by the country generally in that wonderful body of water known as the Great Salt lake, there is also great ignorance shown by outside people who endeavor to explain its beauties and advantages.”

In December 1895, Norwegian mining engineer Adolph Beck stepped out of his London flat and was accosted by a woman who accused him of tricking her out of some jewelry. Beck protested his innocence — he had been in Buenos Aires at the time — but the police accused him of an unsolved series of such swindles, and he was sentenced to seven years of penal servitude.

He was paroled in July 1901 and essentially the same thing happened again — a woman accused him of stealing her jewelry, he was arrested, and a jury found him guilty. He was saved only because another man was arrested for the same crime while Beck was awaiting sentencing. Wilhelm Meyer, it turned out, was the real swindler; Beck had been convicted twice for crimes he hadn’t committed.

They set him free and gave him £5,000, but he died a bitter man in 1909.

A letter from John Phillips of the Yale University School of Medicine to the New England Journal of Medicine, Feb. 14, 1991:

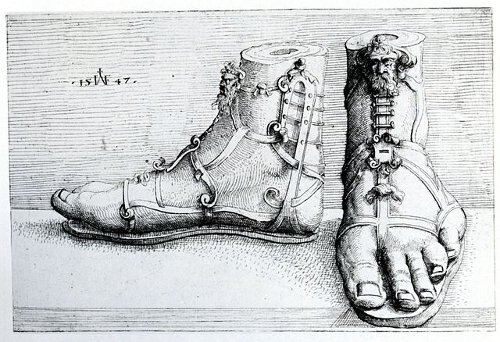

When referring to the hand, the names digitus pollicis, indicis, medius, annularis, and minimus specify the five fingers. In situations of clinical relevance the use of such names can preclude anatomical ambiguity. These time-tested terms have honored the fingers, but the toes have been labeled only by number, except of course the great toe, or hallux. Is it not time for the medical community to have the toes no longer stand up and merely be counted? I submit for consideration the following nomenclature to refer to the pedal digits: for the hallux, porcellus fori; for the second toe, p. domi; for the third toe, p. carnivorus; for the fourth toe, p. non voratus; and for the fifth toe, p. plorans domum.

Using porcellus as the diminutive form of porcus, or pig, one can translate the suggested terminology as follows: piglet at market, piglet at home, meat-eating piglet, piglet having not eaten, and piglet crying homeward, respectively.

(Thanks, Scott.)

Last November, Jacob and Bonnie Richter of West Palm Beach, Fla., drove their motor home to Daytona Beach to attend an RV rally. Their cat, Holly, bolted when Bonnie’s mother opened the door, and could not be found after several days’ search. Finally the Richters returned home.

On New Year’s Eve, Holly was spotted “barely standing” in a backyard about a mile from the Richters’ house in West Palm Beach. The 4-year-old tortoiseshell had traveled 200 miles over two months to return to her hometown. She was identified both by the black-and-brown harlequin patterns in her fur and by an implanted microchip.

No one is quite sure how cats navigate across such long distances. Like other animals they may rely to some extent on magnetic fields, olfactory cues, and the sun, but generally cat navigation seems surest over short distances. In a 1954 study in Germany, cats were placed in a circular maze with exits positioned every 15 degrees; a cat exited most reliably in the direction of home if home was less than 5 kilometers away.

But at least some cats are capable of much greater feats. British cat biologist Roger Tabor cites “Ninja,” a cat who found his way from Mill Creek, Wash., to his old home in Farmington, Utah, in 1997; Howie, an indoor Persian cat who was left with relatives and traveled 1,000 miles across Australia to return to his family’s home in 1978; and a Russian tortoiseshell who traveled 325 miles from Moscow to her owner’s mother’s house in Voronezh in 1989.

Those exploits, and Holly’s, remain unexplained. “We haven’t the slightest idea how they do this,” cat behaviorist Jackson Galaxy told the New York Times in January. “Anybody who says they do is lying, and, if you find it, please God, tell me what it is.”

A letter from Lewis Carroll to Gertrude Chataway, Oct. 28, 1876:

My Dearest Gertrude,

–You will be sorry, and surprised, and puzzled, to hear what a queer illness I have had ever since you went. I sent for the doctor, and said, ‘Give me some medicine, for I’m tired.’ He said, ‘Nonsense and stuff! You don’t want medicine: go to bed!’ I said, ‘No; it isn’t the sort of tiredness that wants bed. I’m tired in the face.’

He looked a little grave, and said, ‘Oh, it’s your nose that’s tired: a person often talks too much when he thinks he knows a great deal.’ I said, ‘No, it isn’t the nose. Perhaps it’s the hair.’

Then he looked rather grave, and said, ‘Now I understand: you’ve been playing too many hairs on the pianoforte.’ ‘No, indeed I haven’t!’ I said, ‘and it isn’t exactly the hair: it’s more about the nose and chin.’

Then he looked a good deal graver, and said, ‘Have you been walking much on your chin lately?’ I said, ‘No.’ ‘Well!’ he said, ‘it puzzles me very much. Do you think it’s in the lips?’ ‘Of course!’ I said. ‘That’s exactly what it is!’

Then he looked very grave indeed, and said, ‘I think you must have been giving too many kisses.’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘I did give one kiss to a baby child, a little friend of mine.’ ‘Think again,’ he said; ‘are you sure it was only one?’ I thought again, and said, ‘Perhaps it was eleven times.’ Then the doctor said, ‘You must not give her any more till your lips are quite rested again.’ ‘But what am I to do?’ I said, ‘because you see, I owe her a hundred and eighty-two more.’

Then he looked so grave that tears ran down his cheeks, and he said, ‘You may send them to her in a box.’ Then I remembered a little box that I once bought at Dover, and thought I would some day give it to some little girl or other. So I have packed them all in it very carefully. Tell me if they come safe or if any are lost on the way.

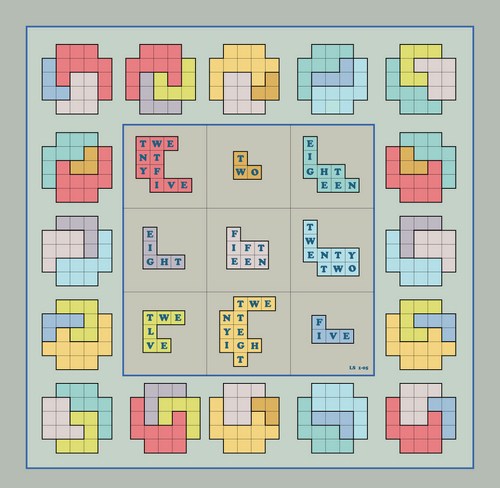

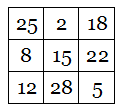

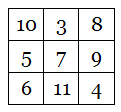

In 1986 Lee Sallows invented the alphamagic square — spell out each number in this magic square and count its letters (25 -> TWENTY-FIVE -> 10), and you’ll produce another magic square:

David Brooks points out that this works also in Pig Latin.

Sallows extends the idea into geometry: