During the hyperinflation that followed World War I in the Weimar Republic, a 5,000-mark cup of coffee could cost 8,000 marks by the time it was drunk. Newspapers published the stupefying multipliers by which prices had risen each day:

Tramway fare: 50,000

Tramway monthly season ticket:

— For one line: 4 million

— For all lines: 12 million

Taxi-autos: multiply ordinary fare by: 600,000

Horse cabs: multiply ordinary fare by: 400,000

Bookshops: multiply ordinary price by: 300,000

Public baths: multiply ordinary price by: 115,000

Medical attendance: multiply ordinary price by: 80,000

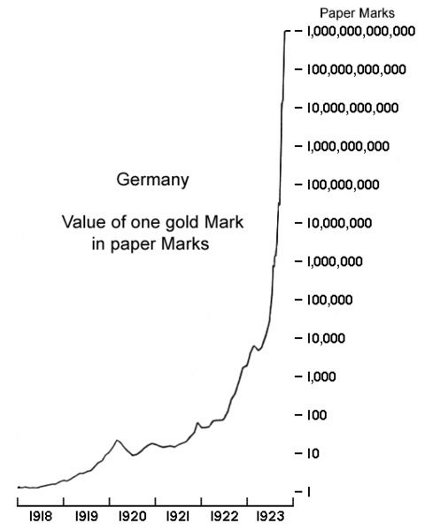

By the end of 1923 there were 92,844,720,742,927,000,000 marks circulating in the German economy, nearly 93 quintillion (note the logarithmic scale in the chart above).

This had a curious psychological effect. In December Time reported, “With the price of bread running into billions a loaf the German people have had to get used to counting in thousands of billions. This, according to some German physicians, brought on a new nervous disease known as ‘zero stroke,’ or ‘cipher stroke,'” a “desire to write endless rows of [zeros] and engage in computations more involved than the most difficult problems in logarithms.”

Human minds are not made to comprehend such large numbers. Foreign minister Walther Rathenau called it the “delirium of milliards”: “What is a milliard? Does a wood contain a milliard leaves? Are there a milliard blades of grass in a meadow? Who knows? If the Tiergarten were to be cleared and wheat sown upon its surface, how many stalks would grow?”

Fortunately the madness was stemmed with the introduction of a new currency — in 1924 one could exchange a trillion of the old marks for a single new Rentenmark, and the economy was finally stabilized.