John Cage’s 4’33” is commonly described as “four and a half minutes of silence,” but in fact it’s the opposite — Cage hoped to lead the audience to hear the ambient sounds of the concert hall as music, to accept as art sounds that they wouldn’t normally consider in that way.

“What they thought was silence, because they didn’t know how to listen, was full of accidental sounds,” he said of the piece’s 1952 premiere. “You could hear the wind stirring outside during the first movement. During the second, raindrops began pattering on the roof, and during the third the people themselves made all kinds of interesting sounds as they talked or walked out.”

In a broad sense 4’33” was Cage’s most significant work, but the notion of a dedicated piece of art with no substance does introduce some perplexing puzzles. The work debuted as a piano piece with a specified length, but Cage later said that “the work may be performed by any instrumentalist or combination of instrumentalists and last any length of time,” and indeed he produced varying scores in different notations. Can all of these be said to be the same piece?

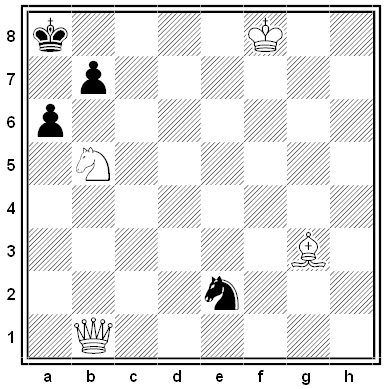

The “In Futurum” movement for solo piano from Czech composer Erwin Schulhoff’s 1919 Fünf Pittoresken consists entirely of rests, but directs the performer to play “the entire song with as much expression and feeling as you like, always, right to the end!” (French pianist Philippe Bianconi wondered, “Should I just sit there?”) And Alphonse Allais’s 1897 Funeral March for the Obsequies of a Deaf Man, below, consists of 24 blank measures. Could an unwitting audience member distinguish either of these from Cage’s work?

A puzzle by philosopher Patricia Werhane of Loyola University of Chicago: Suppose that a pianist were engaged to perform 4’33” but had to withdraw at the last moment, and in desperation the stage manager sat in his place. Would this be a performance of Cage’s work? Would it be a musical performance?

Now more than 60 years old, Cage’s idea may still be too novel for a wide public. When BBC Radio 3 broadcast the first U.K. orchestral performance of 4’33” in 2004, the network had to turn off an emergency backup system that would have interpreted the silence as dead air — and begun playing music.