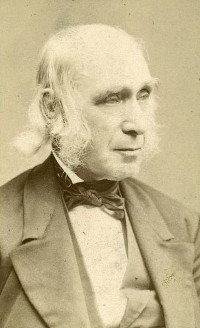

Educator Bronson Alcott punished students by making them punish him:

“One day I called up before me a pupil eight or ten years of age, who had violated an important regulation of the school. All the pupils were looking on, and they knew what the rule of the school was. I put the ruler into the hand of that offending pupil; I extended my hand; I told him to strike. The instant the boy saw my extended hand, and heard my command to strike, I saw a struggle begin in his face. A new light sprang up in his countenance. A new set of shuttles seemed to be weaving a new nature within him. I kept my hand extended, and the school was in tears. The boy struck once, and he himself burst into tears. I constantly watched his face, and he seemed in a bath of fire, which was giving him a new nature. He had a different mood toward the school and toward the violated law. The boy seemed transformed by the idea that I should take chastisement in place of his punishment. He went back to his seat, and ever after was one of the most docile of all the pupils in that school, although he had been at first one of the rudest.”

Some of this may have been wishful thinking. Alcott’s grand ideas were often poorly received, and he found it a struggle to support his family, including daughter Louisa May. He once told his mother he was “still at my old trade — hoping.”