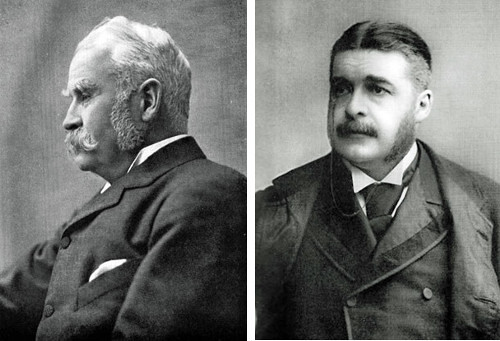

In 1869, composer Frederic Clay introduced W.S. Gilbert to Arthur Sullivan.

“I am very pleased to meet you, Mr. Sullivan,” said Gilbert, “because you will be able to settle a question which has just arisen between Mr. Clay and myself. My contention is that when a musician who is master of many instruments has a musical theme to express, he can express it as perfectly upon the simple tetrachord of Mercury (in which there are, as we all know, no diatonic intervals whatever) as upon the more elaborate disdiapason (with the familiar four tetrachords and the redundant note) which (I need not remind you) embraces in its simple consonance all the single, double, and inverted chords.”

This was gobbledegook that Gilbert had simply cooked up; he wanted to see whether it would “pass muster with a musician.”

Sullivan asked him to repeat the question, then politely said he would like to think it over before making a reply. In 1891 Gilbert said, “I believe he is still engaged in hammering it out.”