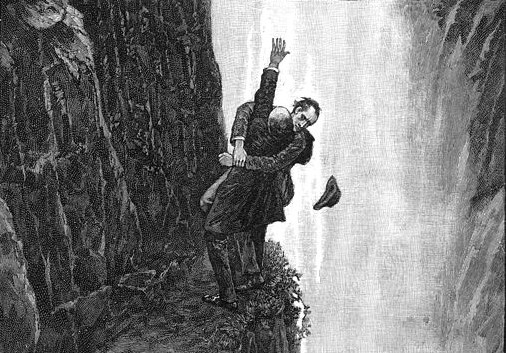

Sherlock Holmes is walking through the valley of Reichenbach Fall. On a clifftop overhead, Moriarty has perched a boulder. When he pushes it, it will have a 90 percent chance of killing Holmes. Just as he is about to send it over the edge, Watson arrives at the clifftop. Watson can’t see Holmes, so he’s not able to push the boulder safely clear, but he reasons that it’s better to push the boulder in a random direction than to let Moriarty aim it carefully. So he pushes the boulder off the cliff in such a way that Holmes’ chance of dying is reduced to 10 percent.

Unfortunately the boulder crushes Holmes anyway. Watson’s push decreased the chance of Holmes’ death, but it also caused it.

What are we to make of this? Generally speaking, it seems true to say that Pre-emptive pushing prevents death by crushing. That is, Watson’s push was of the sort that made it less likely that Holmes would die — if the scenario were re-enacted many times, with the boulder pushed sometimes by Watson, sometimes by Moriarty, Watson-type pushes would result in fewer deaths. But it also seems true to say that Watson’s pushing the rock caused Holmes to die. But cause and prevent are antonyms. How can both of these statements be true?

(Christopher Read Hitchcock, “The Mishap at Reichenbach Fall: Singular vs. General Causation,” Philosophical Studies, June 1995.)