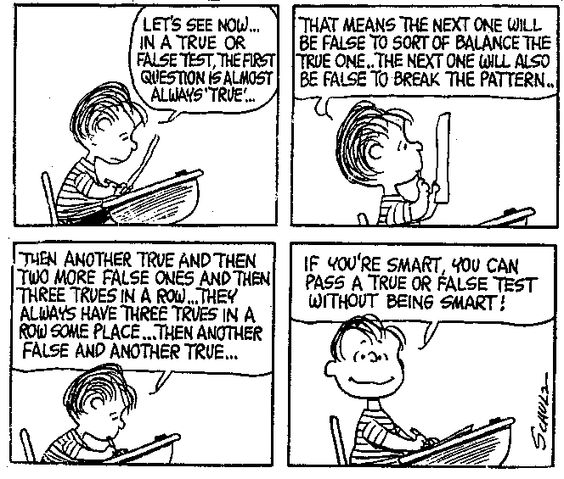

In 1978, inspired by this Peanuts cartoon, Nathaniel Hellerstein invented the Linus sequence, a sequence of 1s and 2s in which each new entry is chosen the prevent the longest possible pattern from emerging at the end of the line. Start with 1:

1

Now if the second digit were also a 1 then we’d have a repeating pattern. So enter a 2:

1 2

If we choose 2 for the third entry we’ll have “2 2” at the end of the line, another emerging pattern. Prevent that by choosing 1:

1 2 1

Now what? Choosing 2 would give us the disastrously tidy 1 2 1 2, so choose 1 again:

1 2 1 1

But now the 1s at the end are looking rather pleased with themselves, so choose 2:

1 2 1 1 2

And so on. The rule is to avoid the longest possible “doubled suffix,” the longest possible repeated string of digits at the end of the sequence. For example, choosing 1 at this point would give us 1 2 1 1 2 1, in which the end of the sequence (indeed, the entire sequence) is a repeated string of three digits. Choosing 2 avoids this, so we choose that.

Admittedly, this isn’t exactly the sequence that Linus was describing in the comic strip, but it opens up a world of its own with many surprising properties (PDF), as these things tend to do.

It’s possible to compile a related sequence by making note of the length of each repetition that you avoided in the Linus sequence. That’s called the Sally sequence.