In Germany, where modern forestry began, a curious new sort of literature arose in the 18th century:

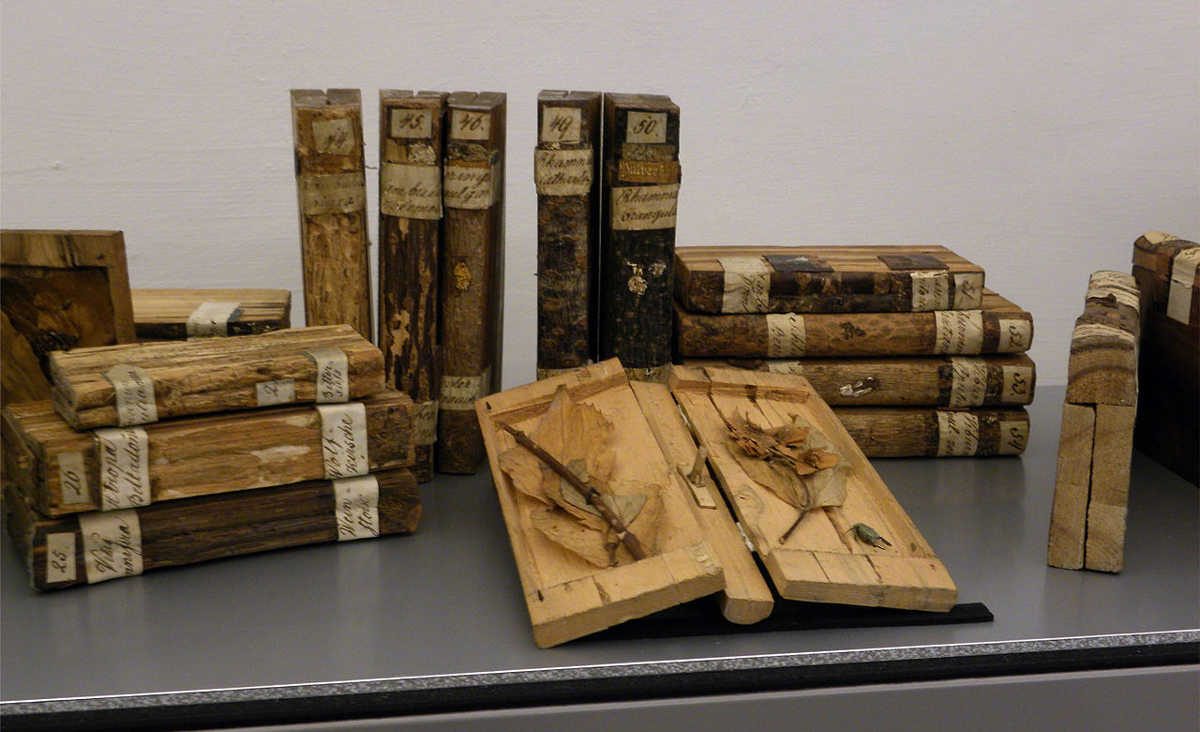

Some enthusiast thought to go one better than the botanical volumes that merely illustrated the taxonomy of trees. Instead the books themselves were to be fabricated from their subject matter, so that the volume on Fagus, for example, the common European beech, would be bound in the bark of that tree. Its interior would contain samples of beech nuts and seeds; and its pages would literally be its leaves, the folios its feuilles.

That’s from Simon Schama’s Landscape and Memory, 1995. These xylotheques, or wood repositories, grew up throughout the developed world — the largest, now held by the U.S. Forest Service, houses 60,000 samples. “But the wooden books were not pure caprice, a nice pun on the meaning of cultivation,” Schama writes. “By paying homage to the vegetable matter from which it, and all literature, was constituted, the wooden library made a dazzling statement about the necessary union of culture and nature.”