Canadian science writer Grant Allen’s 1889 essay “Seven-Year Sleepers” contains an eye-opening passage:

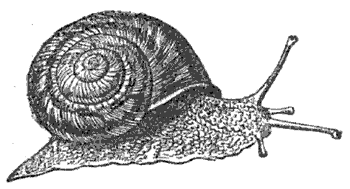

A certain famous historical desert snail was brought from Egypt to England as a conchological specimen in the year 1846. This particular mollusk (the only one of his race, probably, who ever attained to individual distinction), at the time of his arrival in London, was really alive and vigorous; but as the authorities of the British Museum, to whose tender care he was consigned, were ignorant of this important fact in his economy, he was gummed, mouth downward, on to a piece of cardboard, and duly labelled and dated with scientific accuracy, ‘Helix desertorum, March 25, 1846.’ Being a snail of a retiring and contented disposition, however, accustomed to long droughts and corresponding naps in his native sand-wastes, our mollusk thereupon simply curled himself up into the topmost recesses of his own whorls, and went placidly to sleep in perfect contentment for an unlimited period. Every conchologist takes it for granted, of course, that the shells which he receives from foreign parts have had their inhabitants properly boiled and extracted before being exported; for it is only the mere outer shell or skeleton of the animal that we preserve in our cabinets, leaving the actual flesh and muscles of the creature himself to wither unobserved upon its native shores. At the British Museum the desert snail might have snoozed away his inglorious existence unsuspected, but for a happy accident which attracted public attention to his remarkable case in a most extraordinary manner. On March 7, 1850, nearly four years later, it was casually observed that the card on which he reposed was slightly discoloured; and this discovery led to the suspicion that perhaps a living animal might be temporarily immured within that papery tomb. The Museum authorities accordingly ordered our friend a warm bath (who shall say hereafter that science is unfeeling!), upon which the grateful snail, waking up at the touch of the familiar moisture, put his head cautiously out of his shell, walked up to the top of the basin, and began to take a cursory survey of British institutions with his four eye-bearing tentacles. So strange a recovery from a long torpid condition, only equalled by that of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, deserved an exceptional amount of scientific recognition. The desert snail at once awoke and found himself famous. Nay, he actually sat for his portrait to an eminent zoological artist, Mr. [A.N.] Waterhouse; and a woodcut from the sketch thus procured, with a history of his life and adventures, may be found even unto this day in Dr. [S.P.] Woodward’s ‘Manual of the Mollusca,’ to witness if I lie.

This appears to be true: Samuel Peckworth Woodward’s 1851 Manual of the Mollusca contains the portrait above, marked “From a living specimen in the British Museum, March, 1850,” and James Hamilton’s 1854 Excelsior describes the snail’s return to life: “The specimen was immediately detached, and immersed in tepid water. After the lapse of a period not exceeding ten minutes, the animal began to move, put forth its horns, and cautiously emerged from its shell. In a few minutes more it was walking along the surface of the basin in which it was placed. The last time it had exercised its locomotive faculty was in the sandy plains of Egypt, not far from the banks of the Nile.”

Hamilton says it spent the rest of its existence in a glass enclosure, feasting on cabbage and taking an eight-month nap in 1851. It died finally in March 1852. “Such was the end of the Egyptian snail, and it was with some feeling of regret that its death was recorded.”

(Via Metafilter.)