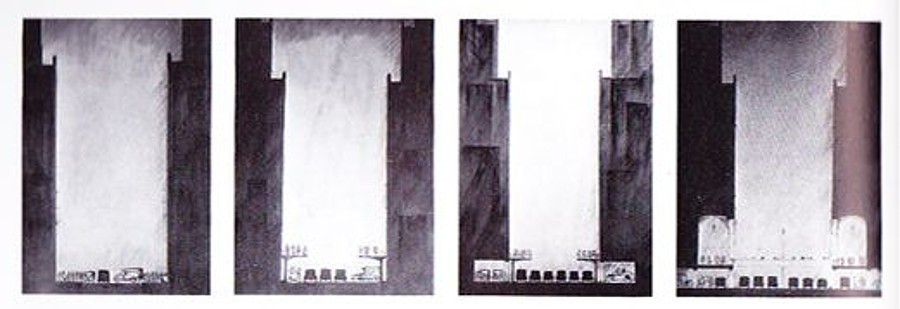

In 1923 Columbia University architect Harvey Wiley Corbett proposed a novel solution to Manhattan’s traffic problem: surrender. His Proposals for Relieving Traffic Congestion in New York had four phases:

- The present situation.

- Pedestrians are transferred from street level to bridges that are cantilevered from the buildings, and patronize shops at this level.

- “Cut-ins” in the buildings permit six cars to move abreast, with parking space for two cars on each side.

- In the end the city’s entire ground level would be an ocean of cars, increasing traffic potential 700 percent, while pedestrians crossed streets on overhead bridges.

Corbett took a strangely romantic view of this: “The whole aspect becomes that of a very modernized Venice, a city of arcades, plazas and bridges, with canals for streets, only the canals will not be filled with real water but with freely flowing motor traffic, the sun glistening on the black tops of the cars and the buildings reflecting in this waving flood of rapidly rolling vehicles.”

By 1975, Corbett wrote, Manhattan could be a network of 20-lane streets in which pedestrians walk from “island” to “island” in a “system of 2,028 solitudes.” That doesn’t feel so different from what we have today.

Related: The city of Guanajuato, Mexico, is built on extremely irregular terrain, and many of the streets are impassable to cars. To compensate, the residents have converted underground drainage ditches and tunnels into roadways (below). These had been dug for flood control during colonial times, but modern dams have left them dry. (Thanks, David.)