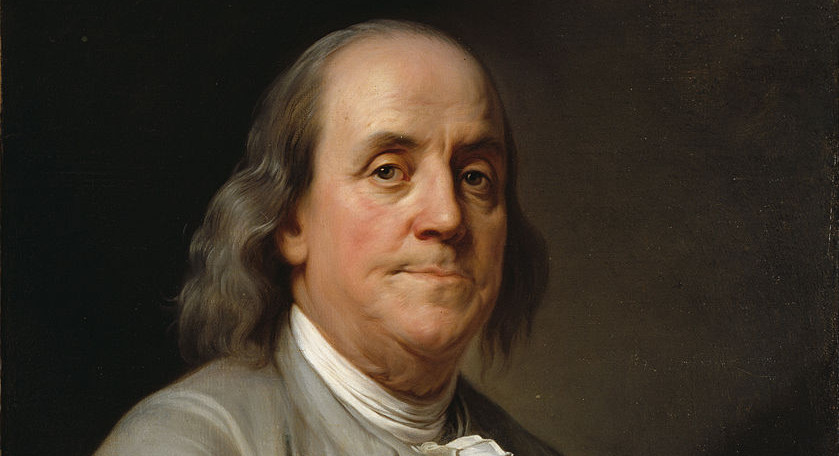

In his autobiography, Benjamin Franklin describes mollifying a rival legislator in the Pennsylvania statehouse:

Having heard that he had in his library a certain very scarce and curious book, I wrote a note to him, expressing my desire of perusing that book, and requesting he would do me the favour of lending it to me for a few days. He sent it immediately, and I return’d it in about a week with another note, expressing strongly my sense of the favour. When we next met in the House, he spoke to me (which he had never done before), and with great civility; and he ever after manifested a readiness to serve me on all occasions, so that we became great friends, and our friendship continued to his death.

This seems to be a real psychological phenomenon — you can sometimes more reliably make a friend by asking a favor than by doing one, or, as Franklin put it, “He that has once done you a kindness will be more ready to do you another, than he whom you yourself have obliged.”

In a 1969 study, subjects who had won money in a question-and-answer competition were asked to return it; those whom the researcher himself approached reported liking him more than those who’d been approached by a secretary. In another study, students were assigned a teaching task using two different methods, one in which they encouraged their students and one in which they insulted and criticized them. In a debriefing they rated the students they’d encouraged to be more likable and attractive than those they’d insulted. That may reveal a converse principle, that we devalue others in order to justify wronging them.

(Jon Jecker and David Landy, “Liking a Person as a Function of Doing Him a Favour,” Human Relations 22:4 [1969], 371-378; John Schopler and John S. Compere, “Effects of Being Kind or Harsh to Another on Liking,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 20:2 (1971), 155.)