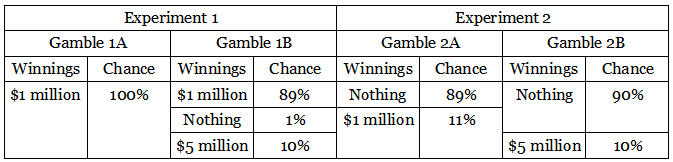

Consider two experiments — in each you’re asked to make a choice between two gambles:

In the first experiment, most people choose Gamble 1A over Gamble 1B. In the second, most people choose Gamble 2B over Gamble 2A. Neither of those choices, in itself, is unreasonable. But economist Maurice Allais pointed out in 1953 that choosing 1A and 2B together does appear inconsistent. To see why, refine the table a bit further:

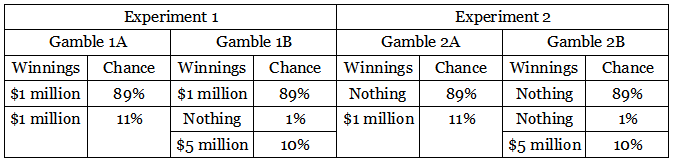

Now it’s clear that, within each experiment, both gambles give the same outcome 89 percent of the time. The only thing to distinguish them, then, is the remaining 11 percent — and when we focus on those segments, Gamble 1A matches Gamble 2A, and 1B matches 2B. Any given individual might tend to prefer a sure thing or a gamble, but here, it seems, most people prefer the sure thing in Experiment 1 and the gamble in Experiment 2.

This doesn’t mean that most people are irrational, Allais argued, but rather that expected utility theory might not reliably predict their behavior.