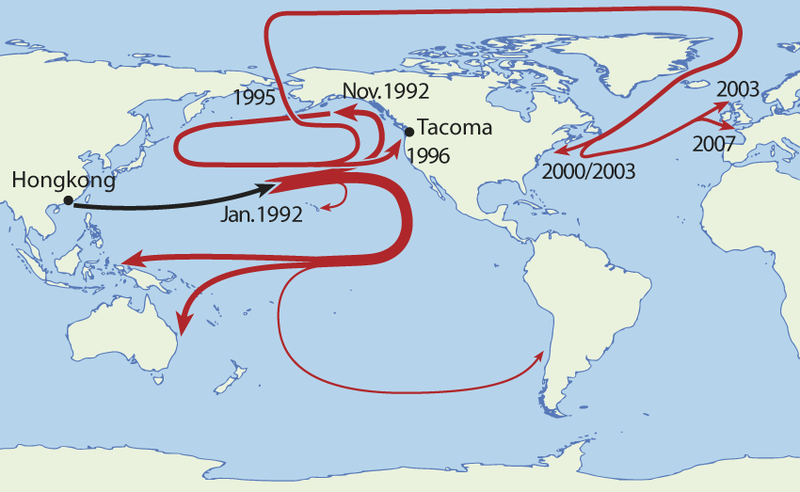

During a storm in January 1992, a container was swept overboard from a ship in the North Pacific. As it happened, it contained 28,800 children’s bath toys, and oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer realized they offered the basis for a serendipitous study of surface currents. Working with his colleague James Ingraham, Ebbesmeyer began to track the toys as they drifted around the globe, accumulating reports from beachcombers, coastal workers, and local residents as they began to wash up on beaches. Using computer models, they were able to predict correctly that toys would make landfall in Washington state, Japan, and Alaska, and even become trapped in pack ice and spend years creeping across the top of the world before making an eventual reappearance in the North Atlantic. “Ultimately,” Ebbesmeyer wrote, “the toys will turn to dust, joining the scum of plastic powder which rides the global ocean.”

For some reason, media accounts of the story always carried the image of a solitary rubber duck, though the toys had also included beavers, turtles, and frogs. “Maybe it’s a kind of racism,” Ebbesmeyer speculated to journalist Donovan Hohn in 2007. “Speciesism.”

See Ambassador.