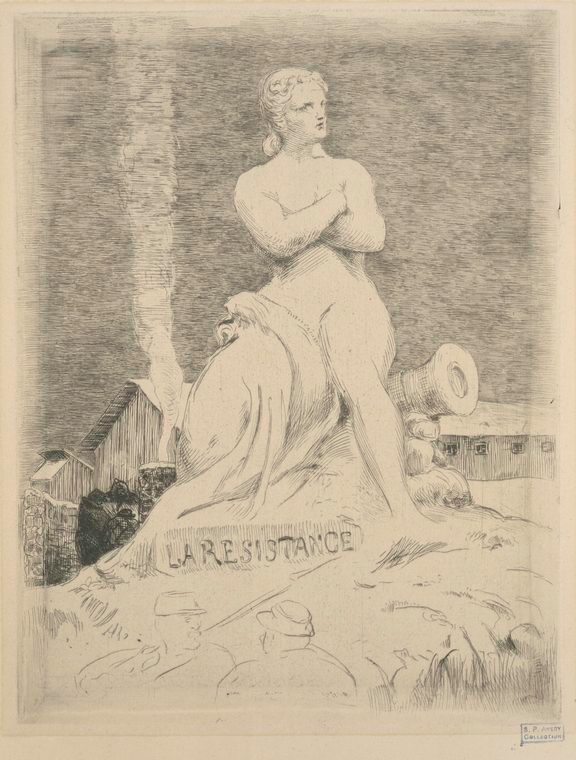

During a lull in the Prussian attack on Paris in December 1870, the Seventh Company of the French National Guard spent a few hours building a “museum” of snow on the southern edge of the city. Among them was 29-year-old sculptor Alexandre Falguière, who spent three hours crafting La Statue de la Résistance, a nine-foot emblem of French resistance in the form of a defiant woman atop a cannon. Félix Philippoteaux sketched the snow woman, Théophile Gautier wrote an essay, Théodore de Banville published a poem, Félix Bracquemond made an etching, and Faustin Betbeder produced a series of lithographs, but none of these captured the essence of the original. Falguière promised to make a permanent version in plaster or marble, but it never appeared. Critic H. Galli wrote in L’Art français in 1895:

As soon as Falguière was back in his studio, he took up his modeling knife, but he sought, worked, and suffered in vain. None of his maquettes had the proud allure, the poetry of his snow statue; he destroyed them. The capitulation, the dismemberment of France, and then the awful civil war had, alas, dissipated his last hopes. The inspiration was dead.

“Recapturing that magic would prove to be impossible for the unflagging Falguière,” writes Bob Eckstein in The History of the Snowman. “Eventually he created many variations in wax, plaster, terra cotta, and bronze, ranging in size from two to four feet high, all less successful than the original snow sculpture. Falguière could never duplicate the spontaneity and urgency of that long-gone snow woman. That moment had passed and had melted along with his original masterpiece.”