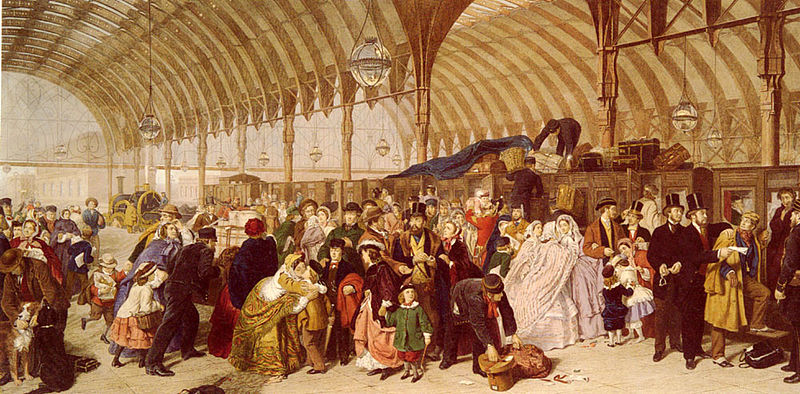

Is this art? It’s The Railway Station, painted by William Powell Frith in 1862. In his 1914 book Art, critic Clive Bell singled out Frith’s painting to claim that it wasn’t art at all. Why? Bell said it lacks “significant form,” which he defined as “lines and colours combined in a particular way, certain forms, and relations of forms, that stir our aesthetic emotions.” Frith’s painting, he said, provoked pleasant feelings in him but no aesthetic emotion:

Few pictures are better known or liked than Frith’s Paddington Station: certainly I should be the last to grudge it its popularity. Many a weary forty minutes have I whiled away disentangling its fascinating incidents and forging for each an imaginary past and an improbable future. But certain though it is that Frith’s masterpiece, or engravings of it, have provided thousands with half-hours of curious and fanciful pleasure, it is not less certain that no one has experienced before it one half-second of aesthetic rapture — and this although the picture contains several pretty passages of color, and is by no means badly painted. Paddington Station is not a work of art; it is an interesting and amusing document in which line and color are used to recount anecdotes, suggest ideas and indicate the manners and customs of an age: they are not used to provoke aesthetic emotion.

Was he right? Notably, in a 2012 survey of 105 art professionals, not one agreed with him: 97% of the respondents said they felt Frith’s painting was art, and the remaining 3% were unsure.

“Admittedly, these data do not prove that Bell’s theory is wrong,” the authors note. “The sensibilities required to detect significant form and experience the aesthetic emotion it provokes could be even rarer than Bell claimed.”

(Richard Kamber and Taylor Enoch, “Why Is That Art?”, in Florian Cova and Sébastien Réhault, Advances in Experimental Philosophy of Aesthetics, 2019.)