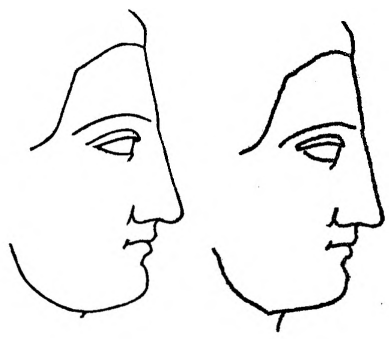

Francis Galton was interested in communicating with Mars as early as 1892, when he wrote a letter to the Times suggesting that we try flashing sun signals at the red planet. At a lecture the following year he described more specifically a method by which pictures might be encoded using 26 alphabetical characters, which could then be transmitted over a distance in 5-character “words,” in effect creating a low-resolution visual telegraph. As a study he reduced this profile of a Greek girl to 271 coded dots, which he found yielded “a very creditable production.”

This had huge implications, he felt. In 1896 he imagined a whole correspondence with a civilization of intelligent ants on Mars; in three and a half hours they catch our attention; teach us their base-8 mathematical notation; demonstrate their shared understanding of certain celestial bodies and mathematical constants; and finally propose a specified 24-gon in which points can be situated by code, like stitches in a piece of embroidery.

That opens a limitless avenue for colloquy — the Martians send images of Saturn, Earth, the solar system, and domestic and sociological drawings, a new one every evening. Galton concludes that two astronomical bodies that are close enough to signal one another with flashes of light already have everything they need to establish “an efficient inter-stellar language.”