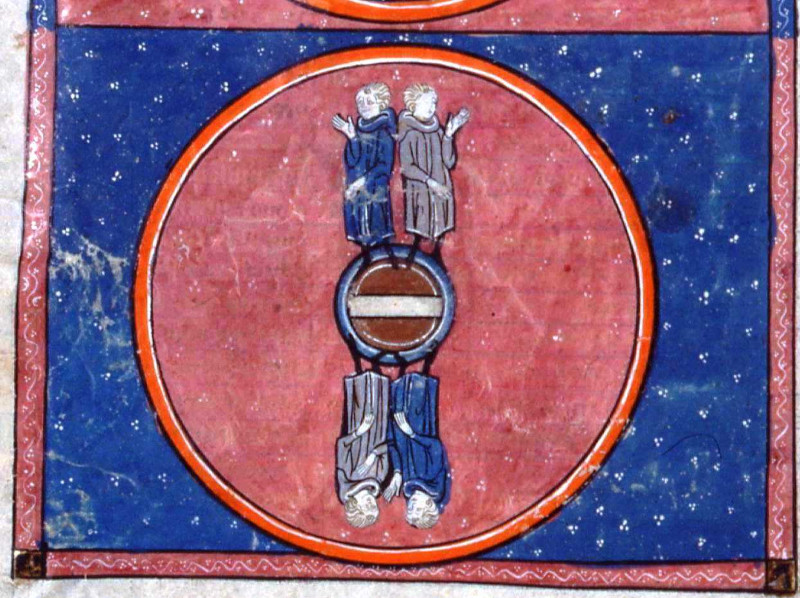

How is it with those who imagine that there are antipodes opposite to our footsteps? Do they say anything to the purpose? Or is there any one so senseless as to believe that there are men whose footsteps are higher than their heads? Or that the things which with us are in a recumbent position, with them hang in an inverted direction? That the crops and trees grow downwards? That the rains, and snow, and hail fall upwards to the earth? And does any one wonder that hanging gardens are mentioned among the seven wonders of the world, when philosophers make hanging fields, and seas, and cities, and mountains?

— Lactantius, Institutiones Divinae, 303