An American reporter discovered this inscription on the wall of a Verdun fortress in 1945:

Austin White–Chicago, Ill.–1918

Austin White–Chicago, Ill.–1945

This is the last time I want to write my name here.

An American reporter discovered this inscription on the wall of a Verdun fortress in 1945:

Austin White–Chicago, Ill.–1918

Austin White–Chicago, Ill.–1945

This is the last time I want to write my name here.

remugient

adj. bellowing again

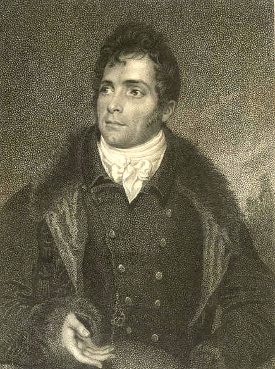

Robert Coates (1772-1848) achieved his dream of becoming a famous actor. Unfortunately, he was famous for being bad — like William McGonagall, Coates was so transcendently, world-bestridingly awful at his chosen craft that he attracted throngs of jeering onlookers.

In one performance of Romeo and Juliet, when he gave his exit line, “O, let us hence; I stand on sudden haste,” his diamond-spangled costume dropped a buckle and he began to hunt for it on hands and knees. “Come off, come off!” hissed the stage manager. “I will as soon as I have found my buckle,” he replied.

And that was a good night. He regularly improvised his lines; he took snuff during Juliet’s speeches and shared it with the audience; he tried to break into the Capulet tomb with a crowbar; he was pelted with carrots and oranges; he dragged Juliet from the tomb “like a sack of potatoes”; and he died on request, several times a night, always first sweeping the stage with his handkerchief. (“You may laugh,” he told one audience, “but I do not intend to soil my nice new velvet dress upon these dirty boards.”)

Once, having been killed in a stage duel, he overheard one woman wonder whether his diamonds were real. He sat up, bowed to her, said, “I can assure you, madam, on my word and honor they are,” and died again.

‘”No,” she laughed.’ How on earth could that be done? If you try to laugh and say ‘No’ at the same time, it sounds like neighing — yet people are perpetually doing it in novels. If they did it in real life they would be locked up.

— Hilaire Belloc, “On People in Books,” 1910

“If you can count your money, you don’t have a billion dollars.” — J. Paul Getty

“Nobody who has to ask what a yacht costs has any business owning one.” — J.P. Morgan

“A man who has a million dollars is as well off as if he were rich.” — John Jacob Astor

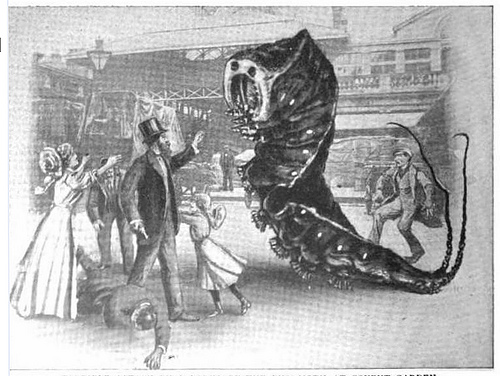

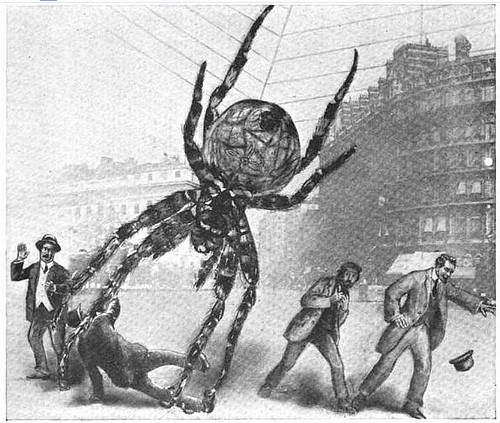

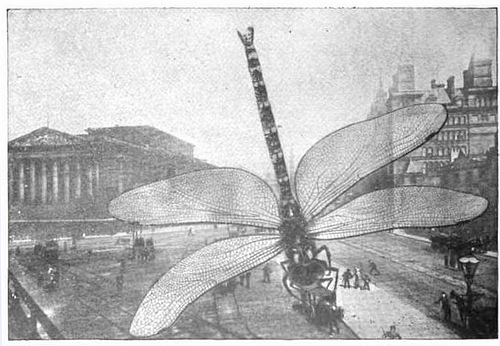

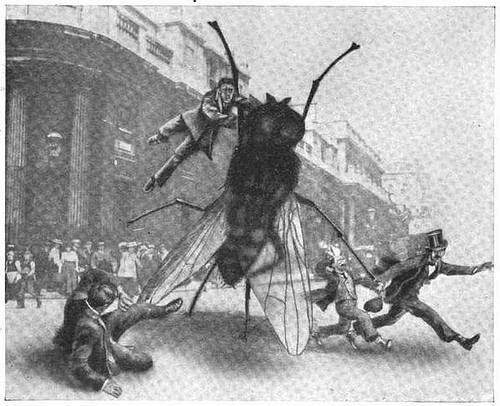

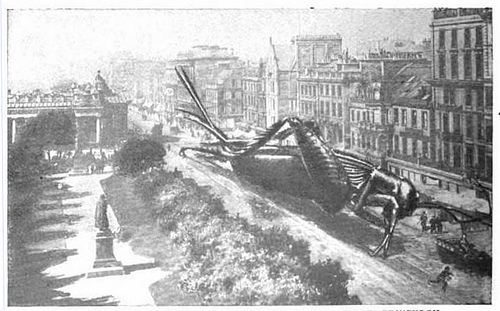

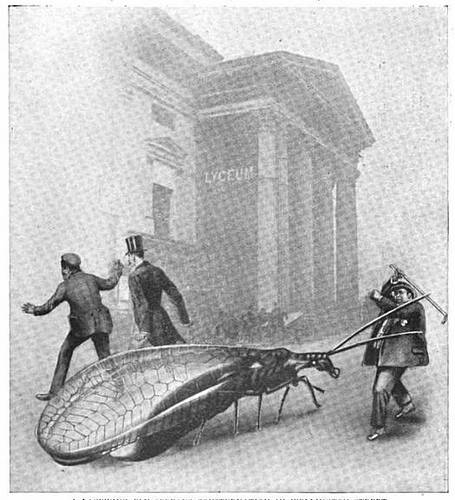

The Strand Magazine ran an alarming feature in 1910: “If Insects Were Bigger.” The editors inserted photographs of ordinary English insects into contemporary Edwardian street scenes, with pretty terrifying results. “What a terrible calamity, what a stupefying circumstance, if mosquitoes were the size of camels, and a herd of wild slugs the size of elephants invaded our gardens and had to be shot with rifles!”

“Panic Caused by a Mosquito in Piccadilly Circus.”

“Terrible Attack by a Larva of the Puss-Moth at Covent Garden.”

“The Araneus Diadema Spider Descends Upon Trafalgar Square.”

“Fierce Onslaught by an Earwig in St. James’s Street.”

“A Dragon-Fly Captures an Unsuspecting Four-Wheeler in Liverpool.”

“Exploits of a House-Fly at the Bank of England.”

“A Leviathan Grasshopper’s Arrival in Princes Street, Edinburgh.”

“A Lacewing Fly Spreads Consternation in Wellington Street.”

Author J.H. Kerner-Greenwood wrote: “It is true we are still molested by hordes of wild animals of bloodthirsty propensities. These wild animals only lack the single quality–namely, that of size–to render them all-powerful and all-desolating, and this quality they have not been able to attain owing to the lack of favouring conditions.” Mothra turned up 51 years later.

So recently as 1860 some gay spirits in London put their heads together and perpetrated a successful and notorious piece of foolery on the wholesale plan. Towards the latter part of March many well-known persons received through the post the following invitation card, bearing the stamp of an inverted sixpence on one of the corners for official effect:

‘Tower of London–Admit Bearer and Friend to view annual ceremony of Washing the White Lions on Sunday, April 1, 1860. Admittance only at White Gate. It is particularly requested that no gratuities be given to wardens or attendants.’

The ruse worked so well that a succession of cabs rattled around Tower Hill all the morning, much to the disturbance of the customary peace of the Sabbath, in vain attempts to discover the White Gate.

— William Shepard Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs, 1898

The Gospel of Luke contains a parable about a rich man and a beggar. Both men die, and the rich man is consigned to hell while the beggar is received into the bosom of Abraham. The rich man pleads for mercy, but Abraham tells him that in his lifetime he received good things and the beggar evil things: “now he is comforted and thou art tormented.” The rich man then begs that his brothers be warned of what lies in store for them, but Abraham rejects this plea as well, saying, “If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded though one rose from the dead.”

Now, writes E.V. Milner:

Suppose … that this last request of Dives had been granted; suppose, in fact, that some means were found to convince the living, whether rich men or beggars, that ‘justice would be done’ in a future life, then, it seems to me, an interesting paradox would emerge. For if I knew that the unhappiness which I suffer in this world would be recompensed by eternal bliss in the next world, then I should be happy in this world. But being happy in this world I should fail to qualify, so to speak, for happiness in the next world. Therefore, if there were such a recompense awaiting me, its existence would seem to entail that I should at least be not wholly convinced of its existence.

“Put epigrammatically, it would appear that the proposition ‘Justice will be done’ can only be true for one who believes it to be false. For one who believes it to be true justice is being done already.”

“We would often be sorry if our wishes were gratified.” — Aesop