Author: Greg Ross

The King’s Salary

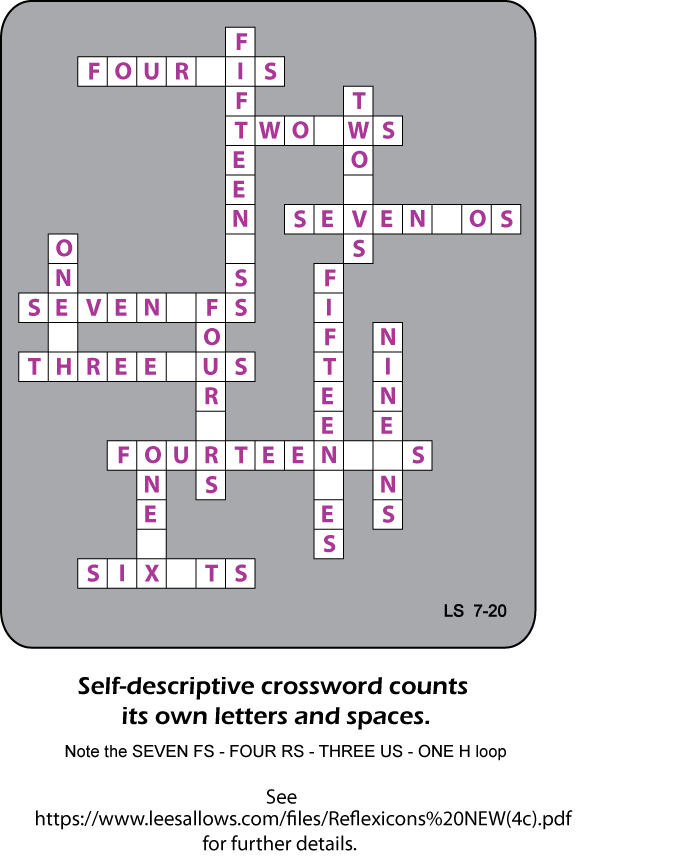

A little kingdom contains 66 people, a king and 65 citizens. Each of them, including the king, has a salary of one gold piece. When democracy comes, the king is denied a vote, but he has the power to suggest changes, in particular regarding the redistribution of salaries. The salaries must total 66, and each salary must be a whole number of gold pieces. The citizens will vote on each suggestion, which will pass if more citizens vote for it than against it. Each voter will reliably support a measure if it will increase his salary, oppose it if it will decrease his salary, and otherwise abstain from voting.

The king is greedy. What’s the highest salary he can arrange for himself?

Piece Work

Now this last example is very interesting. What happened when Christ broke the bread at the Last Supper? He broke a thing into fragments. But each piece contained the whole: that is, his entire body. And, again, what happens if the Host, after it has been consecrated by a priest, falls to the floor of the church and crumbles, and if a mouse then eats the crumbs? Does the mouse eat Christ’s body? I do not wish to develop this argument, merely to remind you that this was one of the arguments used by Protestant reformers to ridicule Catholic practice.

— Jacqueline Lichtenstein, “The Fragment: Elements of a Definition,” in William Tronzo, ed., The Fragment: An Incomplete History, 2009

Pledge

One night in 1939, Wolcott Gibbs’ 4-year-old son Tony began chanting a song in the bathtub. It was sung “entirely on one note except that the voice drops on the last word in every line”:

He will just do nothing at all.

He will just sit there in the noonday sun.

And when they speak to him, he will not answer them,

Because he does not care to.

He will stick them with spears and throw them in the garbage.

When they tell him to eat his dinner, he will just laugh at them.

And he will not take his nap, because he does not care to.

He will not talk to them, he will not say nothing.

He will just sit there in the noonday sun.

He will go away and play with the Panda.

He will not speak to nobody because he doesn’t have to.

And when they come to look for him they will not find him.

Because he will not be there.

He will put spikes in their eyes and put them in the garbage.

And put the cover on.

He will not go out in the fresh air or eat his vegetables.

Or make wee-wee for them, and he will get thin as a marble.

He will do nothing at all.

He will just sit there in the noonday sun.

Pete Seeger liked this so much that he made a song of it — he called it “Declaration of Independence”:

Inside Job

Here’s a unit square. Prove that, if nine points are identified in the square’s interior, we can always find three of them that form a triangle of area 1/8 or less.

Dead End

Hong Kong contains a street named Rednaxela Terrace. It’s hard not to notice that this is Alexander spelled backward, but the origin of the name is uncertain.

In Signs of a Colonial Era (2009), Andrew Yanne and Gillis Heller claim that the street had been named Alexander Terrace after its original owner but that a clerk recorded the name backward, as the Chinese language was written right to left at the time.

Another possibility is that the name is linked to New York abolitionist Robert Alexander Young’s 1829 pamphlet Ethiopian Manifesto, which contains the name Rednaxela.

Fair Play

In writing novels as well as plays the cardinal rule is to treat the various characters as if they were chessmen, and not try to win the game by altering the rules; for instance, not move the knight as if it were a pawn, and so on. Again the characters ought to be strictly defined, and not put out of action in order to help the author to accomplish his purpose; for, on the contrary, it is through their activity alone he should try to win. Not to do this is to appeal to the miraculous, which is always unnatural.

Mirror Numbers

A puzzle by A. Vasin from the July-August 1993 issue of Quantum:

Two numbers are mirror numbers if each presents the digits of the other in reverse order, such as 123 and 321. Find two mirror numbers whose product is 92,565.

Unquote

“Should a garden look as if the gardener worked on his knees? I ask you.” — Lincoln Steffens

Fancy That

In 2005 Yale psychologists Deena Skolnick and Paul Bloom asked children and adults about the beliefs of fictional characters regarding other characters — both those that exist in the same world, such as Batman and Robin, and those that inhabit different worlds, such as Batman and SpongeBob SquarePants.

They found that while both adults and young children distinguish these two types of relationships, young children “often claim that Batman thinks that Robin is make-believe.”

“This is a surprising result; it seems unlikely that children really believe that Batman thinks Robin is not real,” they wrote. “If they did, they should find stories with these characters incomprehensible.”

One possible explanation is that young children can find it hard to take a character’s perspective, and so might have been answering from their own point of view rather than Batman’s. In a second study, kids acknowledged that characters from the same world can act on each other.

But this is a complex topic even for grownups. “James Bond inhabits a world quite similar to our own, and so his beliefs should resemble those of a real person. Like us, he should think Cinderella is make-believe. On the other hand, Cinderella inhabits a world that is sufficiently dissimilar to our own that its inhabitants should not share many of our beliefs. Our intuition, then, is that Cinderella should not believe that James Bond is make-believe; she should have no views about him at all.”

(Deena Skolnick and Paul Bloom, “What Does Batman Think About Spongebob? Children’s Understanding of the Fantasy/Fantasy Distinction,” Cognition 101:1 [2006], B9-B18. See Author!, Truth and Fiction, and Split Decision.)