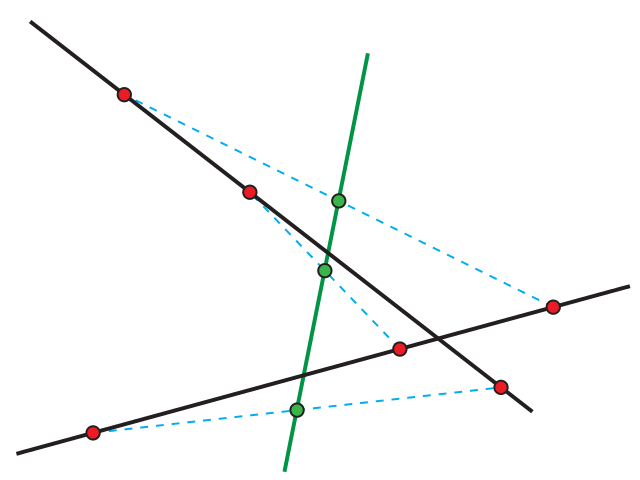

Utopian socialist Robert Owen opposed corporal punishment, so when he took over the textile mill at New Lanark, Scotland, in 1800, he kept order with a “silent monitor”: Over each worker’s machine was hung a block whose successive sides were painted white, yellow, blue, and black:

The 2,500 toys had their positions arranged every day, according to the conduct of each worker during the preceding day: white indicating superexcellence; yellow, moderate goodness; blue, a neutral condition of morals; and black, exceeding naughtiness.

These ratings were assigned by the departmental overseer, whose own rating was assigned by an under-manager. The final say lay with Owen, to whom workers could appeal, and the daily ratings were recorded in a “book of character” maintained by each department.

This sounds draconian, but combined with Owen’s generous nature it seemed to work. “As time went on,” wrote one biographer, “the yellows and whites gained on the darker hues; and in the later stages of Owen’s management the signs were almost entirely white, with a sprinkling of yellows.”