“Moreover, the satellites of Jupiter are invisible to the naked eye, and therefore can exercise no influence over the Earth, and therefore would be useless, and therefore do not exist.” — Astronomer Francesco Sizzi, on Galileo’s claim to have seen the moons of Jupiter

Author: Greg Ross

Ill-Starred

For stewardess Violet Jessop, bad luck came in threes. In 1911 she was working on the RMS Olympic when it collided with a British warship off the Isle of Wight.

A few months later she took a position on the Titanic, which sank famously in the North Atlantic in 1912. Her lifeboat was picked up by the Carpathia.

And in 1916 she was working as a nurse on the hospital ship Britannic when it struck a mine in the Aegean Sea and went down.

By this time she was philosophical. Though the Britannic sank in less than 50 minutes, she took care to rescue her toothbrush, “because there had always been much fun at my expense after the Titanic, when I complained of my inability to get a toothbrush on the Carpathia. I recalled [my brother’s] joking advice: ‘Never undertake another disaster without first making sure of your toothbrush.'”

After that her bad luck ceased. She lived without incident for another 55 years and died of heart failure in 1971.

Figures

294 miles south of Paradise, Michigan … is Hell, Michigan.

Garage Talk

In 1950, General Motors condensed the sounds of car trouble into seven types:

- The Rattle. A series of hard, sharp sounds in rapid succession, like a hard object being shaken around in a metal container. This noise usually indicates a loose or broken part striking against another.

- The Thump. A dull sound, generally made when a soft part strikes against a hard part. An example is the noise made by a deflated tire on the road.

- The Squeak. A sharp, shrill, piercing noise, generally made by two dry metal parts rubbing together. The sound may be sharp and erratic, or drawn out — a squeal. Lack of lubrication causes many squeaks.

- The Grind. This is a continuous crushing sound like a part being crushed between two revolving parts. Such a sound might come from the transmission.

- The Knock. This is a sharper and more distinct sound than a thump. It’s generally associated with a loose rod or crankshaft bearing. (Not to be confused with the “knock” or ping of a laboring engine.)

- The Scrape. A grating or harsh rubbing sound, often made by two pieces of material rubbing together. The sound of a dragging brake could be described as a scrape.

- The Hiss. This is like escaping air or steam or the sound of water on a hot metal part.

The idea was to simplify conversations between mechanics and customers. “Besides telling what the noise is, the driver is expected to report where it comes from and when it happened,” explained Popular Science. “With this report, the mechanic has a good start toward learning why it happened.”

Tickets, Please

At the Kishi railway station in southern Japan, the stationmaster has her own litter box. Tama, a local stray cat, was named to the post in January 2007, and ridership immediately jumped 17 percent.

She’s paid in cat food and gets her own hat; as the station is unmanned, her main job is to greet passengers.

This all sounds remarkably progressive, but Tama may have mixed feelings: She’s still the only female manager in the company.

“An Extraordinary Shot”

A Clergyman, in the eastern part of Sussex, a few years since, at a single discharge of his gun, killed a partridge, shot a man, a hog, and a hogsty, broke fourteen panes of glass, and knocked down six gingerbread kings and queens that were standing on the mantle-piece opposite the window. The above may be depended upon as a fact, not exaggerated, but given literally as it happened.

— Pierce Egan, Sporting Anecdotes, Original and Selected, 1822

In a Word

pogonotrophy

n. the growing of a beard

The Handicapper

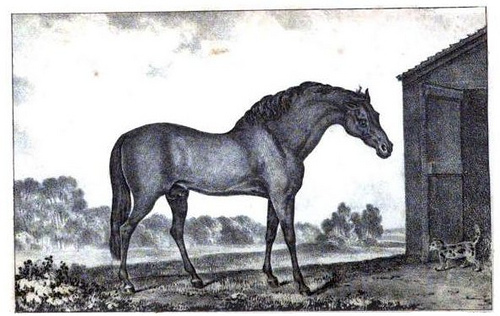

In the 1740s, workers at a stable near Cambridge noticed that a cat had taken a peculiar fancy to one of the horses there. She was always near him, they found, sitting on his back or nestling nearby in the manger.

Her attachment proved so great that when the stallion died in 1754 “she sat upon him after he was dead in the building erected for him, and followed him to the place where he was buried under a gateway near the running stable; sat upon him there till he was buried, then went away, and never was seen again, till found dead in the hayloft” — apparently of grief.

The cat’s name is not recorded, but she certainly could pick horses: The stallion was the Godolphin Arabian, now revered as the founder of modern thoroughbred racing stock. His direct descendants include both Seabiscuit and Man o’ War.

A Long Wait

In 1912, workmen digging a tunnel for New York’s new subway discovered a carpeted room decorated with oil paintings, chandeliers, and a grandfather clock.

According to Tracy Fitzpatrick in Art and the Subway, it was the waiting room for an early prototype subway built in 1870 — a block-long tunnel in which a single car was pushed by a giant fan. Funding had failed, and the project had been forgotten.

A Blindfold Bullseye

In 1908, German novelist Ferdinand H. Grautoff published Banzai!, a curiously prescient account of a war between Japan and the United States. Japan deals a surprise defeat to unprepared American troops, who rally to repulse them:

Our splendid regiments could not be checked, so eager were they to push forward, and they succeeded in storming one of the enemy’s positions after the other along the mountainside. At last the enemy began to retreat, and the thunder of the cannon was again and again drowned in the frenzied cheers. General MacArthur was continually receiving at his headquarters reports of fresh victories in the front and on both wings.

Note the name of the American commander. Grautoff gives no clue to his inspiration, but in an introduction he writes, “All the incidents we had observed on the dusty highway of History, and passed by with indifference, had been sure signs of the coming catastrophe.”