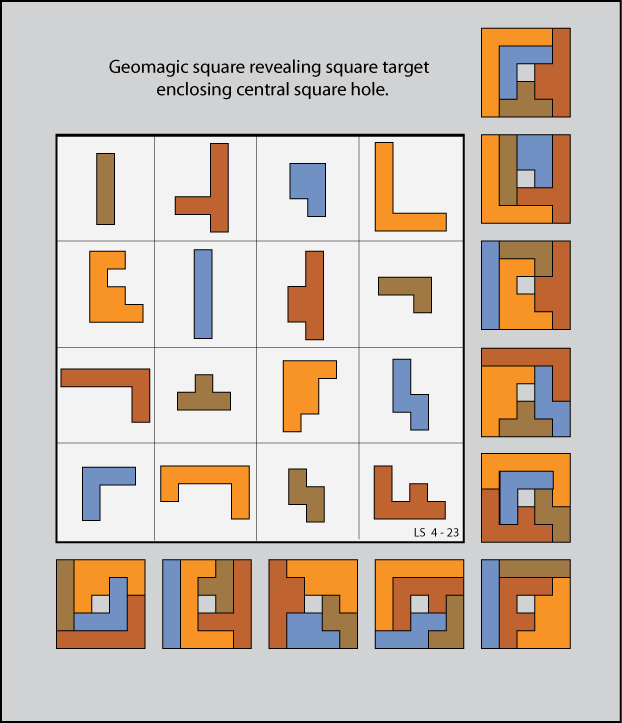

From Lee Sallows:

(Thanks, Lee!)

From Lee Sallows:

(Thanks, Lee!)

From The Book of 500 Curious Puzzles, 1859:

Following is the epitaph of Ellinor Bachellor, an old pie woman. How should we read it?

Bene A. Thin Thed Ustt HEMO. Uld yo

L.D.C. RUSTO! Fnel L.B.

Ach El Lor. Lat. ELY,

Wa. S. shove N. W. How — Ass! kill’d I. N. T. H.

Ear T. Sofp, I, Escu Star.

D. San D T Art. San D K. N E. W. E

Ver — Yus E. — Oft He ove N, W. Hens He

‘Dli V’DL. on geno

Ug H S hem A.D.E. he R. la Stp. Uf — fap

Uf. F. B Y he. R hu

S. Ban D. M.

Uch pra is ‘D. No. Wheres Hedot

HL. i. e. Tom. A kead I.R.T.P. Yein hop Esthathe

R. C. RUSTWI,

L L B. Era is ‘–D!

When John Hollander claimed that English has no rhyme for bilge, George Starbuck imagined advancing on him, calling him a killjoy.

“No don’t!” Hollander cried. “I’m not a killj–“

When quacks with pills political would dope us,

When politics absorbs the livelong day,

I like to think about that star Canopus,

So far, so far away.

Greatest of visioned suns, they say who list ’em;

To weigh it science always must despair.

Its shell would hold our whole dinged solar system,

Nor even know ’twas there.

When temporary chairmen utter speeches,

And frenzied henchmen howl their battle hymns,

My thoughts float out across the cosmic reaches

To where Canopus swims.

When men are calling names and making faces,

And all the world’s ajangle and ajar,

I meditate on interstellar spaces

And smoke a mild seegar.

For after one has had about a week of

The argument of friends as well as foes,

A star that has no parallax to speak of

Conduces to repose.

— Bert Leston Taylor

gliff

n. an unexpected view of something that startles one; a sudden fear

irrision

n. the act of sneering or laughing derisively; mockery; derision

mortiferous

adj. bringing or producing death

proceleusmatic

adj. inciting, animating, or inspiring

Photographer Philippe Halsman took three hours to pose seven women in the shape of a skull for his surrealistic portrait In Voluptas Mors, after a sketch by Salvador Dalí, who’s seen in the foreground. Director Jonathan Demme borrowed the idea for the one-sheet poster for his 1991 film The Silence of the Lambs — the skull image on the “death’s head moth” is a miniature version of the same tableau.

This gruesome portrait illustrates an unconfirmed story: It’s said that in the 16th century a Hungarian nobleman named Gregor Baci survived for a year after being impaled through the head during a joust.

Did this really happen? We don’t know, but in 2010 surgeon Martin Missmann and his colleagues showed that it could have.

They had been presented with a craftsman whose head was transfixed by a metal bar that had fallen from a height of 14 meters. After two surgeries and a year of headaches and double vision, they said, the patient was symptom-free.

“This case shows that even severe penetrating traumas of the head and neck can be survived without sequelae of serious physiological dysfunction,” they wrote.

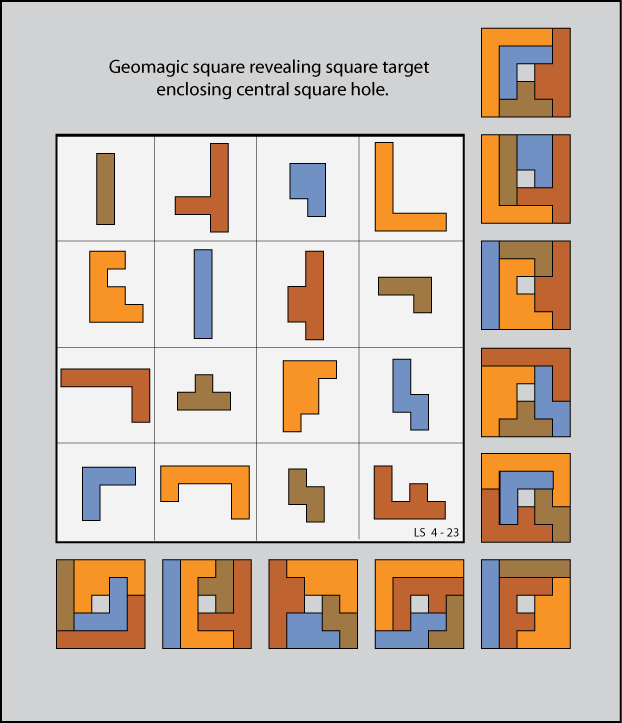

An odd little detail: David Garrick said of Anglican evangelist George Whitefield that he “could make his audience weep or tremble merely by varying his pronunciation of the word ‘Mesopotamia.'”

“Garrick did not say that he had ever seen this feat performed,” noted one biographer. “[H]e surely must have been befooling some too warm admirer of the preacher, to see how much he could believe.”

But Garrick also said, “I would give a hundred guineas if I could only say ‘Oh’ like Mr. Whitefield.”

A young Michelangelo once aged a sculpture artificially to bring a higher price. He began working on a sleeping cupid in 1495, at age 20, apparently inspired by a sculpture in the Medici Gardens. At the advice of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco he aged it falsely to resemble an antique and then passed it on to a dealer, who sold it to Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio. Riario erupted when he discovered the artifice, and Michelangelo offered to take back the sculpture, but the dealer wouldn’t hear of it, and Michelangelo ultimately kept his share of the money.

The work has since been lost, but it helped to establish the artist’s reputation and first brought him to the notice of patrons in Rome.

Qui bibit, dormit; qui dormit, non peccat; qui non peccat, sanctus est; ergo: qui bibit, sanctus est.

He who drinks sleeps; he who sleeps does not sin; he who does not sin is holy; therefore he who drinks is holy.

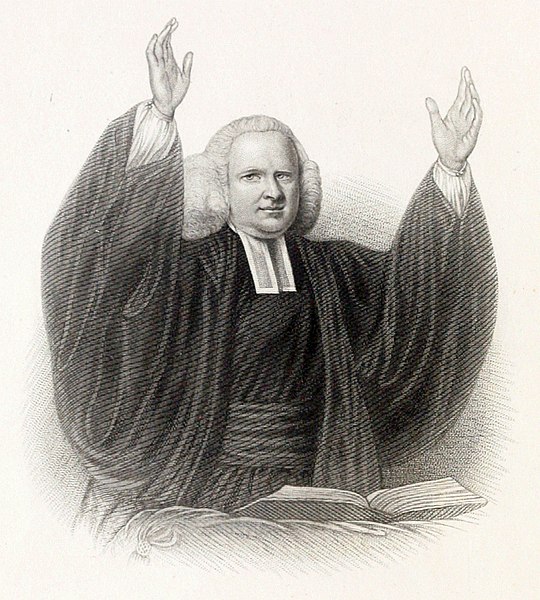

I just found this visual explication of the potato paradox — if potatoes are 99 percent water by weight, and you start with 100 pounds of potatoes and let them dehydrate until they’re 98 percent water, what’s their new weight?

The surprising answer is 50 pounds. Blue boxes represent water, orange non-water. So to double the share of the non-water portion we have to halve the amount of water.

(I had thought it was the setting that made this so confusing, but it turns out real potatoes are 80 percent water! So it’s not as outlandish as I’d thought.)