whelve

v. to cover with an inverted bowl

(Thanks, Ian.)

whelve

v. to cover with an inverted bowl

(Thanks, Ian.)

In 1760, was brought to Avignon, a true lithophagus, or stone-eater. He not only swallowed flints of an inch and a half long, a full inch broad, and half an inch thick; but such stones as he could reduce to powder, such as marble, pebbles, &c. he made into paste, which was to him a most agreeable and wholesome food. I examined this man, says the writer, with all the attention I possibly could; I found his gullet very large, his teeth exceedingly strong, his saliva very corrosive, and his stomach lower than ordinary, which I imputed to the vast number of flints he had swallowed, being about five-and-twenty, one day with another. Upon interrogating his keeper, he told me the following particulars: ‘This stone-eater,’ says he, ‘was found three years ago, in a northern uninhabited island, by some of the crew of a Dutch ship. Since I have had him, I make him eat raw flesh with the stones; I could never get him to swallow bread. He will drink water, wine, and brandy, which last liquor gives him infinite pleasure. He sleeps at least twelve hours in a day, sitting on the ground, with one knee over the other, and his chin resting on his right knee. He smokes almost all the time he is not asleep, or is not eating. The flints he has swallowed, he voids somewhat corroded, and diminished in weight; the rest of his excrements resembles mortar.’

— John Platts, Encyclopedia of Natural and Artificial Wonders and Curiosities, 1876

How hard, when those who do not wish

To lend–that’s lose–their books,

Are snared by anglers–folks that fish

With literary hooks;

Who call and take some favorite tome,

But never read it through;

They thus complete their sett at home,

By making one of you.

I, of my Spenser quite bereft,

Last winter sore was shaken;

Of Lamb I’ve but a quarter left,

Nor could I save my Bacon.

They picked my Locke, to me far more

Than Bramah’s patent worth;

And now my losses I deplore,

Without a Home on earth.

Even Glover’s works I cannot put

My frozen hands upon;

Though ever since I lost my Foote,

My Bunyan has been gone.

My life is wasting fast away;

I suffer from these shocks;

And though I’ve fixed a lock on Gray,

There’s gray upon my locks.

They still have made me slight returns,

And thus my grief divide;

For oh! they’ve cured me of my Burns,

And eased my Akenside.

But all I think I shall not say,

Nor let my anger burn;

For as they have not found me Gay,

They have not left me Sterne.

“Sir Walter Scott said that some of his friends were bad accountants, but excellent book-keepers.”

— Charles Carroll Bombaugh, Gleanings for the Curious From the Harvest-Fields of Literature, 1890

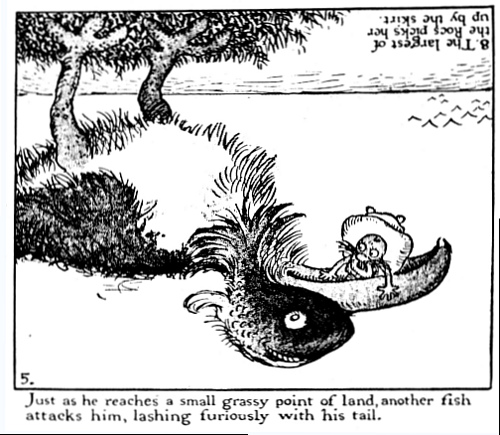

The great thing about Gustave Verbeek’s comic strips is that when you reach the end of a page, you can invert it to see the story continue.

He created 64 such comics for the New York Herald between 1903 and 1905.

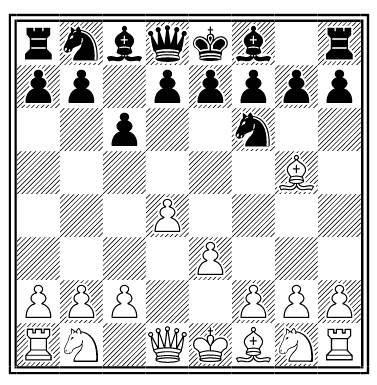

The shortest decisive tournament chess game ever played was Dordevic-Kovacevic, Bela Crkva 1984:

1. d4 Nf6 2. Bg5 c6 3. e3

3. … Qa5+ wins the bishop. Dordevic resigned.

In 1963, an Indiana construction engineer discovered a small hoard of coins on the bank of the Ohio River. Two of them eventually passed to a Clarksville museum, which identified them as Roman coins from the third century.

No one has explained how they came to be there. The engineer who found them said they’d been grouped as though in a leather pouch which had since disintegrated. But his name, and the rest of the hoard, has been lost.

Modern atheists:

“Atheism,” said George Carlin, “is a non-prophet organization.”

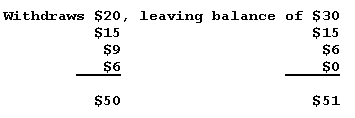

A man deposited $50 in a savings account, then withdrew it in various sums. When he’d recovered his $50 he was surprised to find $1 left in the account, though it had drawn no interest. When he inquired, the bank produced this ledger:

“I’d rather be a failure at something I enjoy than be a success at something I hate.” — George Burns

Anagrams:

THE NUDIST COLONY = NO UNTIDY CLOTHES

A SENTENCE OF DEATH = FACES ONE AT THE END

AN AISLE = IS A LANE

IS PITY LOVE? = POSITIVELY

CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE = CAN RUIN A SELECTED VICTIM

CABARET = A BAR, ETC.

THE ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA = A DICTIONARY CAN BE ELEPHANTIC

GREYHOUND = HEY, DOG, RUN!

H.M.S. PINAFORE = NAME FOR SHIP

COMMITTEES = COST ME TIME

HEARTHSTONES = HEAT’S THRONES

THE DAWNING = NIGHT WANED

A STRIP-TEASER = ATTIRE SPARSE