In October 2005, Neil Armstrong received a letter from a social studies teacher charging that the moon landings had been faked. “[O]ver 30 years on from the pathetic TV broadcast when you fooled everyone by claiming to have walked upon the Moon,” he wrote, “I would like to point out that you, and the other astronauts, are making yourselfs a worldwide laughing stock … Perhaps you are totally unaware of all the evidence circulating the globe via the Internet. Everyone now knows the whole saga was faked, and the evidence is there for all to see.”

Armstrong replied:

Mr. Whitman,

Your letter expressing doubts based on the skeptics and conspiracy theorists mystifies me.

They would have you believe that the United States Government perpetrated a gigantic fraud on its citizenry. That the 400,000 Americans who worked on an unclassified program are all complicit in the deception, and none broke ranks and admitted their deceit.

If you believe that, why would you contact me, clearly one of those 400,000 liars?

I trust that you, as a teacher, are an educated person. You will know how to contact knowledgeable people who could not have been party to the scam.

The skeptics claim that the Apollo flights did not go to the moon. You could contact the experts from other countries who tracked the flights on radar (Jodrell Bank in England or even the Russian Academicians).

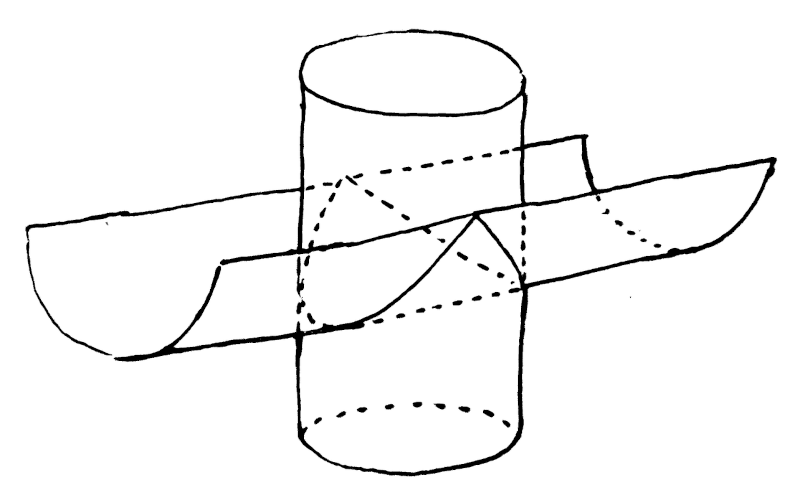

You should contact the Astronomers at Lick Observatory who bounced their laser beam off the Lunar Ranging Reflector minutes after I installed it. Or, if you don’t find them persuasive, you could contact the astronomers at the Pic du Midi observatory in France. They can tell you about all the other astronomers in other countries who are still making measurements from these same mirrors — and you can contact them.

Or you could get on the net and find the researchers in university laboratories around the world who are studying the lunar samples returned on Apollo, some of which have never been found on earth.

But you shouldn’t be asking me, because I am clearly suspect and not believable.

Neil Armstrong

(From James R. Hansen, A Reluctant Icon: Letters to Neil Armstrong, 2020.)