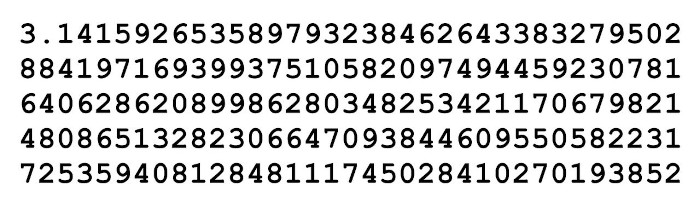

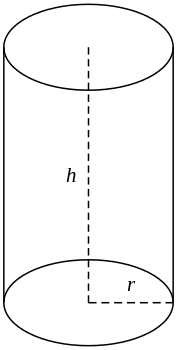

This just caught my eye in an old issue of the Mathematical Gazette, a note from P.G. Wood. Suppose we’re designing a cylinder that’s closed at both ends and must encompass a given volume. What relative dimensions should we give it in order to minimize its surface area?

A young student thought, well, if we slice the cylinder with a plane that passes through its axis, the plane’s intersection with the cylinder will form a rectangle. And if we spin that rectangle, it’ll sweep out the surface area of the cylinder. So really we’re just asking: Among all rectangles of the same area, which has the smallest perimeter? A square. So the cylinder’s height should equal its diameter.

It turns out that’s right, but the student had overlooked something. The fact that the volume of the cylinder is fixed doesn’t imply that the area of the rectangle is fixed. We don’t know that.

Wood wrote, “We seem to have arrived at the right answer by rather dubious means.”

(P.G. Wood, “73.5 Interesting Coincidences?”, Mathematical Gazette 73:463 [1989], 33-33.)