For this final episode of the Futility Closet podcast we have eight new lateral thinking puzzles — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

Intro:

Sears used to sell houses by mail.

Many of Lewis Carroll’s characters were suggested by fireplace tiles in his Oxford study.

The sources for this week’s puzzles are below. In some cases we’ve included links to further information — these contain spoilers, so don’t click until you’ve listened to the episode:

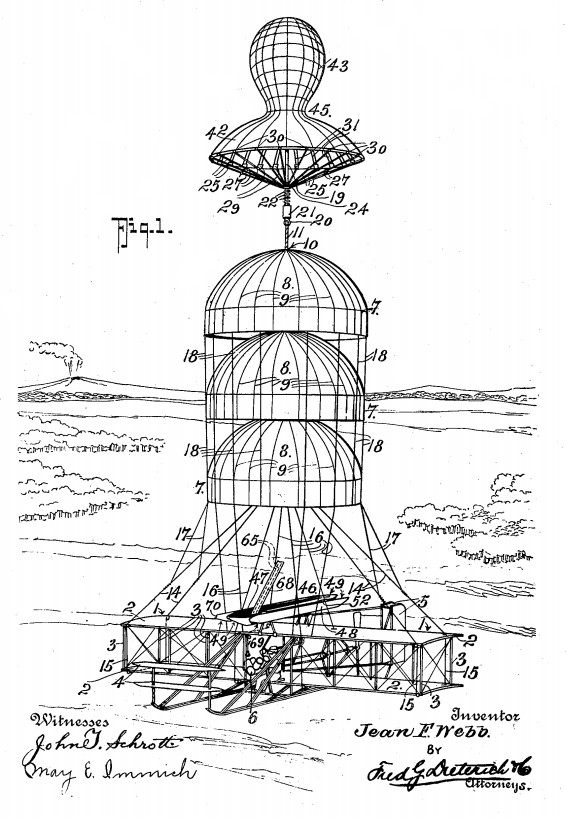

Puzzle #1 is from Greg. Here are two links.

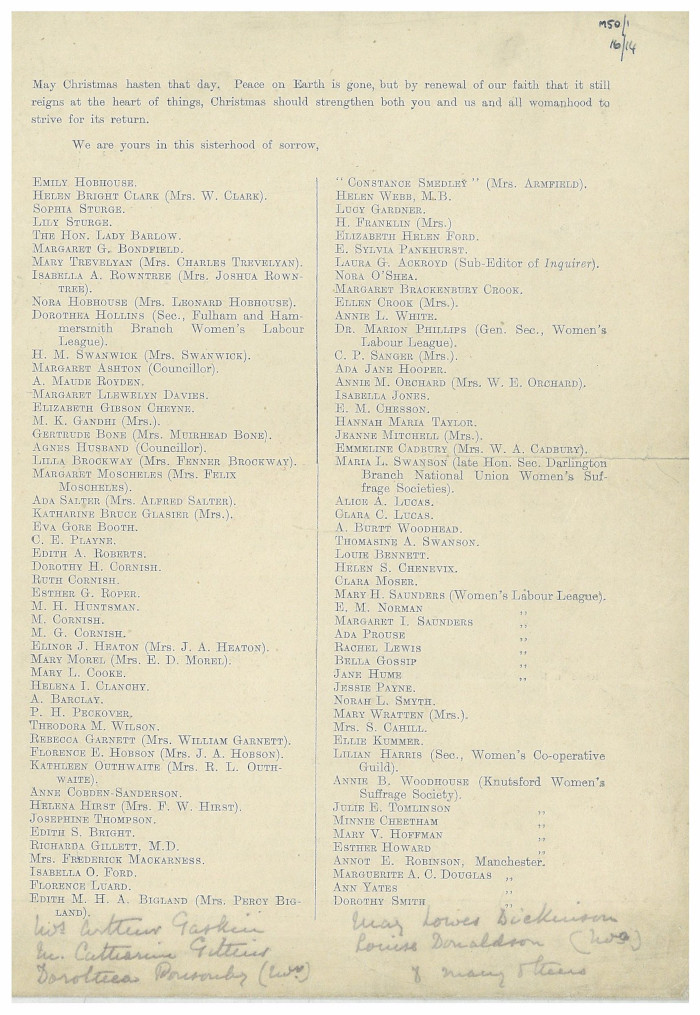

Puzzle #2 is from listener Diccon Hyatt, who sent this link.

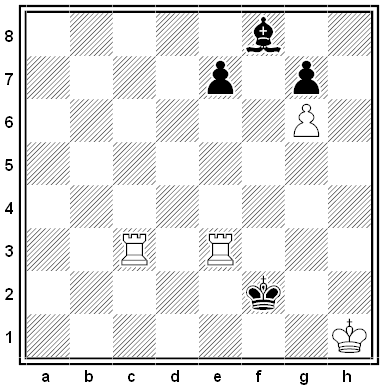

Puzzle #3 is from listener Derek Christie, who sent this link.

Puzzle #4 is from listener Reuben van Selm.

Puzzle #5 is from listener Andy Brice.

Puzzle #6 is from listener Anne Joroch, who sent this link.

Puzzle #7 is from listener Steve Carter and his wife, Ami, inspired by an item in Jim Steinmeyer’s 2006 book The Glorious Deception.

Puzzle #8 is from Agnes Rogers’ 1953 book How Come? A Book of Riddles, sent to us by listener Jon Jerome.

You can listen using the player above, download this episode directly, or subscribe on Google Podcasts, on Apple Podcasts, or via the RSS feed at https://futilitycloset.libsyn.com/rss.

Many thanks to Doug Ross for providing the music for this whole ridiculous enterprise, and for being my brother.

If you have any questions or comments you can reach us at podcast@futilitycloset.com. Thanks for listening!