“When Dr. Barton Warren was informed that Dr. Vowel was dead, he exclaimed, ‘What! Vowel dead? Well, thank heaven it was neither you nor I.'”

— William S. Walsh, Handy-Book of Literary Curiosities, 1892

“When Dr. Barton Warren was informed that Dr. Vowel was dead, he exclaimed, ‘What! Vowel dead? Well, thank heaven it was neither you nor I.'”

— William S. Walsh, Handy-Book of Literary Curiosities, 1892

My will contains directions for my funeral, which will be followed, not by mourning coaches, but by herds of oxen, sheep, swine, flocks of poultry, and a small travelling aquarium of live fish, all wearing white scarves in honour to the man who perished rather than eat his fellow-creatures. It will be, with the single exception of Noah’s Ark, the most remarkable thing of the kind yet seen.

— George Bernard Shaw, letter to The Academy, Oct. 15, 1898

From Howard Dinesman’s Superior Mathematical Puzzles (2003):

How can you measure 9 minutes using two hourglass-style timers, one that measures 4 minutes and the other 7 minutes?

Very high and very low temperature extinguishes all human sympathy and relations. It is impossible to feel affection beyond 78° or below 20° of Fahrenheit; human nature is too solid or too liquid beyond these limits. Man only lives to shiver or to perspire. God send that the glass may fall, and restore me to my regard for you, which in the temperate zone is invariable.

— Sydney Smith, letter to Sarah Austin, July 1836

Twenty-two acknowledged concubines, and a library of sixty-two thousand volumes, attested the variety of his inclinations; and from the productions which he left behind him, it appears that the former as well as the latter were designed for use rather than for ostentation.

— Edward Gibbon, on the Roman emperor Gordian II

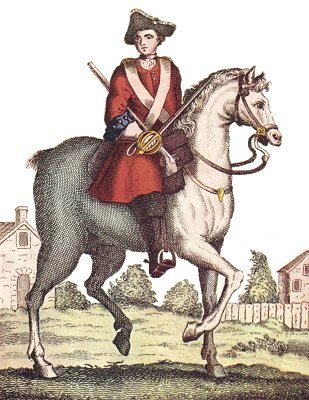

In 1691, on learning that her missing husband was serving in the British Army in Holland, Irish publican Christian Cavanagh disguised herself as a man to go after him. Wounded and captured at the Battle of Landen, she was exchanged back into service, killed another soldier in a duel, was discharged, re-enlisted as a dragoon, and fought with the Scots Greys in the War of the Spanish Succession, all while persuading her fellow soldiers that she was a man.

Author Marian Broderick writes, “[S]he ate with them, drank with them, slept with them, played cards with them, even urinated alongside them by using what she describes as a ‘silver tube with leather straps’. No one was ever the wiser.”

After the Battle of Blenheim she discovered her husband with another woman and decided to remain a dragoon rather than rejoin him. A surgeon finally discovered her secret in 1706, when her skull was fractured in the Battle of Ramillies. Discharged, she served the unit as a sutler until 1712. Hearing the remarkable tale, Queen Anne granted her a bounty of £50 and a shilling a day for the rest of her life.

Lucian, why dost thou lament my death, or call me miserable that am much more happy than thyself? what misfortune is befallen me? Is it because I am not so bald, crooked, old, rotten, as thou art? What have I lost, some of your good cheer, gay clothes, music, singing, dancing, kissing, merry-meetings, thalami lubentias, &c., is that it? Is it not much better not to hunger at all than to eat: not to thirst than to drink to satisfy thirst: not to be cold than to put on clothes to drive away cold? You had more need rejoice that I am freed from diseases, agues, cares, anxieties, livor, love, covetousness, hatred, envy, malice, that I fear no more thieves, tyrants, enemies, as you do.

— Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, 1621

A problem by F. Nazarov, from the November/December 1994 issue of Quantum:

A person with fewer than 10 acquaintances is unsociable. If all your acquaintances are unsociable, you’re a weirdo. If all acquaintanceships are reciprocal (that is, if you know me then I know you), prove that unsociable people outnumber weirdos.

The next important ceremony in which I was officially concerned was the Coronation of King Edward [VII, in 1902]. … Before the Coronation I had a remarkable dream. The State coach had to pass through the Arch at the Horse Guards on the way to Westminster Abbey. I dreamed that it stuck in the Arch, and that some of the Life Guards on duty were compelled to hew off the Crown upon the coach, before it could be freed. When I told the Crown Equerry, Colonel Ewart, he laughed and said, ‘What do dreams matter?’ ‘At all events’, I replied, ‘let us have the coach and the arch measured.’ So this was done; and, to my astonishment, we found that the arch was nearly two feet too low to allow the coach to pass through. I returned to Colonel Ewart in triumph, and said, ‘What do you think of dreams now?’ ‘I think it’s damned fortunate you had one,’ he replied. It appears that the State Coach had not been driven through the arch for some time, and that the level of the road had since been raised during repairs. So I am not sorry that my dinner disagreed with me that night; and I only wish all nightmares were as useful.

That’s from Men Women and Things, the 1937 memoir of William Cavendish-Bentinck, 6th Duke of Portland. An even more striking moment occurred 11 years later, when Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria visited England and the Portlands received him at Welbeck Abbey. During the weeklong visit, Portland and the archduke were shooting on the estate when “one of the loaders fell down. This caused both barrels of a gun he was carrying to be discharged, the shot passing within a few feet of the Archduke and myself. I have often wondered whether the Great War might not have been averted, or at least postponed, had the Archduke met his death then, and not at Sarajevo in the following year.”

A passage from Irene Iddesleigh, by Amanda McKittrick Ros, arguably the worst novel ever written:

‘False woman! Wicked wife! Detested mother! Bereft widow!

‘How darest thou set foot on the premises your chastity should have protected and secured! What wind of transparent touch must have blown its blasts of boldest bravery around your poisoned person and guided you within miles of the mansion I proudly own?

‘What spirit but that of evil used its influence upon you to dare to bend your footsteps of foreign tread towards the door through which they once stole unknown? Ah, woman of sin and stray companion of tutorism, arise, I demand you, and strike across that grassy centre as quickly as you can, and never more make your hated face appear within these mighty walls. I can never own you; I can never call you mother; I cannot extend the assistance your poor, poverty-stricken attire of false don silently requests; neither can I ever meet you on this side the grave, before which you so pityingly kneel!’

Mark Twain called it “one of the greatest unintentionally humorous novels of all time.” The whole thing is here.