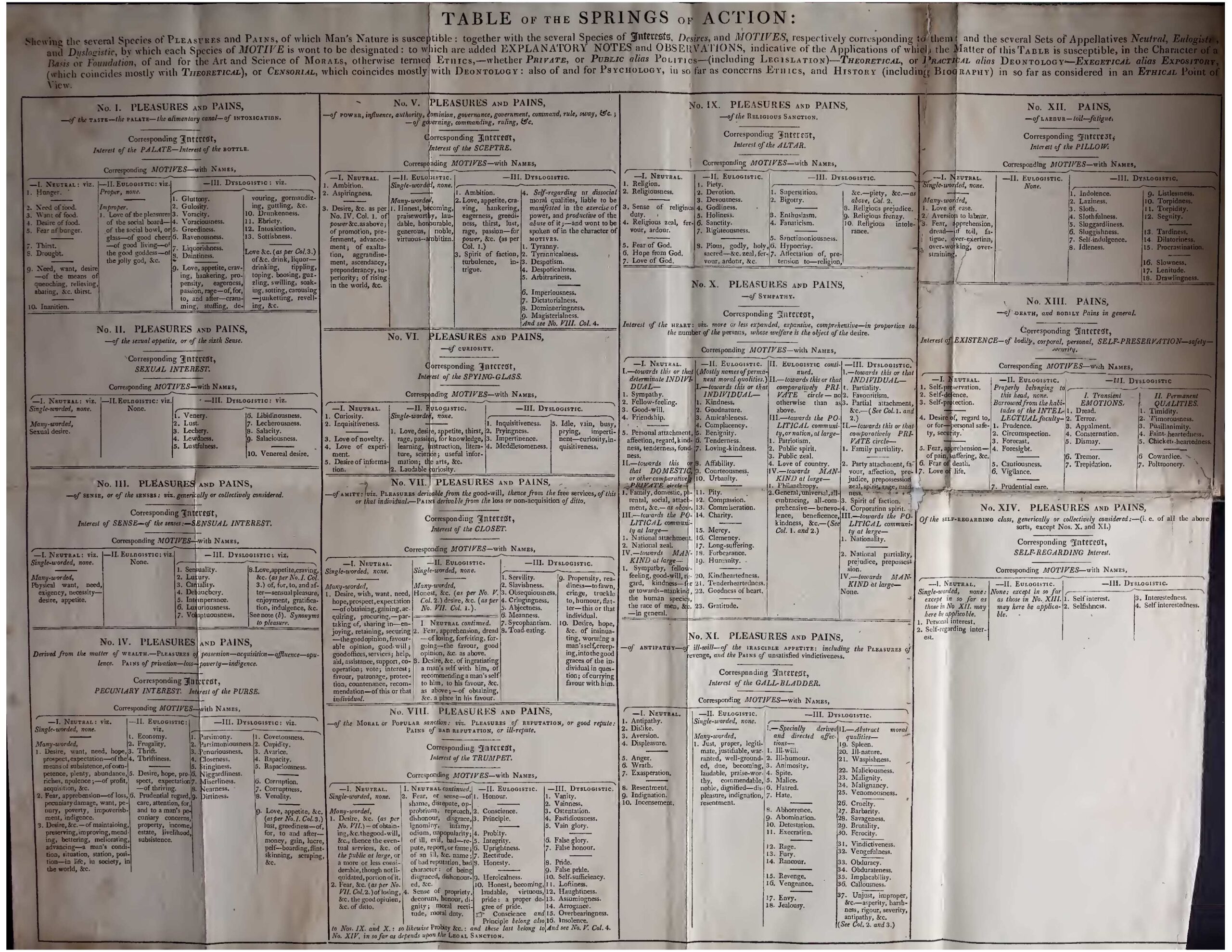

Jeremy Bentham made a table of the springs of action, where every human desire was named in three parallel columns, according as men wish to praise it, to blame it, or to treat it neutrally. Thus we find in one column ‘gluttony,’ and opposite it, in the next column, ‘love of the pleasures of the social board.’ And again, we find in the column giving eulogistic names to impulses, ‘public spirit,’ and opposite to it, in the next column, we find ‘spite.’ I recommend anybody who wishes to think clearly on any ethical topic to imitate Bentham in this particular, and after accustoming himself to the fact that almost every word conveying blame has a synonym conveying praise, to acquire a habit of using words that convey neither praise nor blame.

— Bertrand Russell, Marriage and Morals, 1929

Bentham had published the table in 1817. “By habit,” he wrote, “wherever a man sees a name, he is led to figure to himself a corresponding object, of the reality of which the name is accepted by him, as it were of course, in the character of a certificate. From this delusion, endless is the confusion, the error, the dissension, the hostility, that has been derived.”