Critic Harold C. Schonberg called Leopold Godowsky’s Studies on Chopin’s Études “the most impossibly difficult things ever written for the piano”; Godowsky said they were “aimed at the transcendental heights of pianism.” In the “Badinage,” above, the pianist plays Chopin’s “Black Key” étude with the left hand while simultaneously playing the “Butterfly” étude with the right and somehow preserving the melodies of both. One observer calculated that this requires 1,680 independent finger movements in the space of about 80 seconds, an average of 21 notes per second. “The pair go laughing over the keyboard like two friends long ago separated, now happily united,” marveled James Huneker in the New York World. “After them trails a cloud of iridescent glory.”

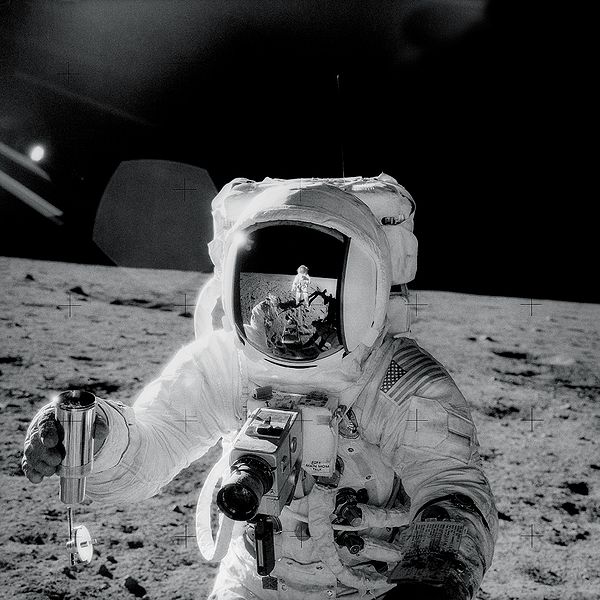

The studies’ difficulty means that they’re rarely performed even today; Schonberg said they “push piano technique to heights undreamed of even by Liszt.” Only Italian pianist Francesco Libetta, above, has performed the complete set from memory in concert.