Speaking of chess, here’s a creditable chess engine written in a single kilobyte of JavaScript.

(Via MetaFilter.)

Speaking of chess, here’s a creditable chess engine written in a single kilobyte of JavaScript.

(Via MetaFilter.)

I’ll tell you a plan for gaining wealth,

Better than banking, trade, or leases;

Take a bank-note and fold it across,

And then you will find your money IN-CREASES!

This wonderful plan, without danger or loss,

Keeps your cash in your hands, and with nothing to trouble it;

And every time that you fold it across,

‘Tis plain as the light of the day that you DOUBLE it!

— Charles Carroll Bombaugh, Gleanings for the Curious From the Harvest-Fields of Literature, 1890

Memory feats of chess master Harry Nelson Pillsbury:

“Philadelphia master and organizer William Ruth told Dale Brandreth that he once sat with Pillsbury at a railroad crossing and wrote down the fairly long and different numbers on each of a large group of passing boxcars while Pillsbury attempted to memorize them. Ruth reported to Brandreth that Pillsbury’s memory for the numbers was incredibly accurate and in the correct order.”

(Eliot Hearst and John Knott, Blindfold Chess: History, Psychology, Techniques, Champions, World Records, and Important Games, 2009.)

{13, 40, 45}

The square of the sum of any two of these numbers minus the square of the third is a square:

(13 + 40)2 – 452 = 282

(13 + 45)2 – 402 = 422

(40 + 45)2 – 132 = 842

(From Edward Barbeau’s Power Play, 1997.)

Paramount photographer A.L. Schafer set up this shot in 1940 to simultaneously flout 10 provisions of the Hays Code, Hollywood’s guideline for self-censorship between 1934 and 1968.

When Schafer entered the photo in an industry competition and organizers threatened him with a fine, he pointed out that the judges were hoarding all 18 prints he’d submitted.

(Via Open Culture.)

03/07/2021 UPDATE: Artist Bruce Timm made a similar image combining nine themes barred from Batman: The Animated Series: guns, drugs, breaking glass, alcohol, smoking, nudity, child endangerment, religion, and strangulation:

In 1998, Walter Hooper, literary advisor of the estate of C.S. Lewis, was asked to summarize the legacy of Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien:

Above all, they were both aware that the type of books they were writing were the type of books they liked to read. As Lewis said on one occasion: ‘I wrote the sort of books I did because they were the sort of books I would have liked to have read when I was growing up.’ When Lewis came across The Hobbit when it was being written he was delighted. This was not only the sort of book he would have liked to have read, but also the sort of book he would like to write. …

They were very honest men. They were not writing to be avant garde. They were writing books that they liked. They, after all, had jobs which left them free so they weren’t depending on writing stories that would sell. In some respects, Tolkien was reluctant to send his work to a publisher so you can hardly call him ambitious for that type of success. They merely wrote the sort of books that they liked which turns out to be the sort of books that many other people like.

From Joseph Pearce, ed., Tolkien — A Celebration: Collected Writings on a Literary Legacy, 2001. Of Middle-earth, Tolkien wrote in a letter, “I had the sense of recording what was already ‘there,’ somewhere; not of ‘inventing.'”

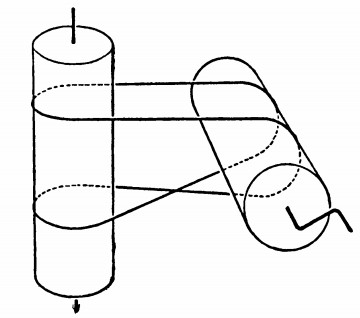

A curious phenomenon noted in Martyn Cundy and A.P. Rollett’s Mathematical Models (1951):

Two rollers are mounted on perpendicular axles in different planes. An endless thread passes round them and connects them, both directly and with a crossover, as shown in the diagram. The instrument is somewhat capricious, but the following phenomena can be demonstrated with it.

(a) One roller is rotated continuously in one direction. The other starts in one direction, but if temporarily stopped with the finger continues in the opposite direction.

(b) One roller is rotated to and fro through a small angle. The other roller rotates continuously in the same direction.

“The apparatus shows that dynamical friction is less than statical, but a full explanation is complicated, if indeed it is possible, and certainly involves consideration of the elasticity of the connecting belt.”

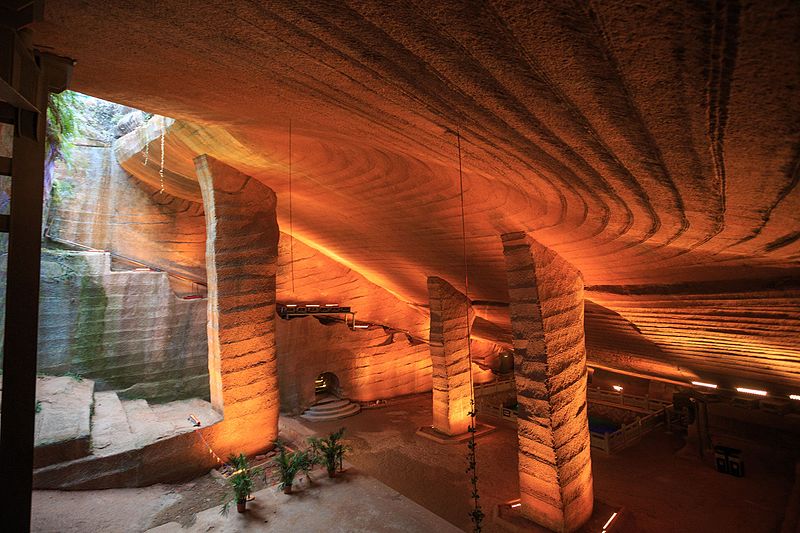

In June 1992, farmers draining ponds in Longyou County, Quzhou prefecture, Zhejiang province, China, discovered that they weren’t ponds at all but drowned caverns, apparently created during the Ming Dynasty.

To date 36 such caves have been discovered in a region of 1 square kilometer. They’ve been compared to underground palaces, with rooms, halls, pillars, beds, bridges, and pavilions. But their age and function remain unclear because no historical document mentions them.

(Cheng Zhu et al., “Lichenometric Dating and the Nature of the Excavation of the Huashan Grottoes, East China,” Journal of Archaeological Science 40:5 [2013], 2485-2492.)

In 2014, Princeton mathematician John Conway proposed a simple conjecture:

Let n be a positive integer. Write the prime factorization in the usual way, e.g. 60 = 22 × 3 × 5, in which the primes are written in increasing order, and exponents of 1 are omitted. Then bring exponents down to the line and omit all multiplication signs, obtaining a number f(n). Now repeat.

So, for example, f(60) = f(22 × 3 × 5) = 2235. Next, because 2235 = 3 × 5 × 149, it maps, under f, to 35149, and since 35149 is prime, we stop there forever.

The conjecture, in which I seem to be the only believer, is that every number eventually climbs to a prime. The number 20 has not been verified to do so. Observe that 20 → 225 → 3252 → 223271 → …, eventually getting to more than one hundred digits without reaching a prime!

Conway offered $1,000 for a counterexample, a number that doesn’t “climb to a prime.” The challenge stood for three years before James Davis, who calls himself “not a mathematician by any stretch,” found the pretty 13532385396179 = 13 × 532 × 3853 × 96179, a composite number that loops onto itself and thus never reaches a prime — a find worth $1,000.

compatchment

n. a thing patched together

emulous

adj. seeking to emulate

concinnity

n. harmony in the arrangement of parts with respect to a whole

featly

adv. neatly