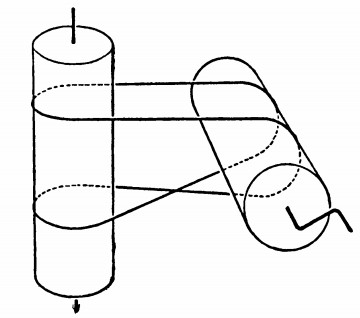

A curious phenomenon noted in Martyn Cundy and A.P. Rollett’s Mathematical Models (1951):

Two rollers are mounted on perpendicular axles in different planes. An endless thread passes round them and connects them, both directly and with a crossover, as shown in the diagram. The instrument is somewhat capricious, but the following phenomena can be demonstrated with it.

(a) One roller is rotated continuously in one direction. The other starts in one direction, but if temporarily stopped with the finger continues in the opposite direction.

(b) One roller is rotated to and fro through a small angle. The other roller rotates continuously in the same direction.

“The apparatus shows that dynamical friction is less than statical, but a full explanation is complicated, if indeed it is possible, and certainly involves consideration of the elasticity of the connecting belt.”