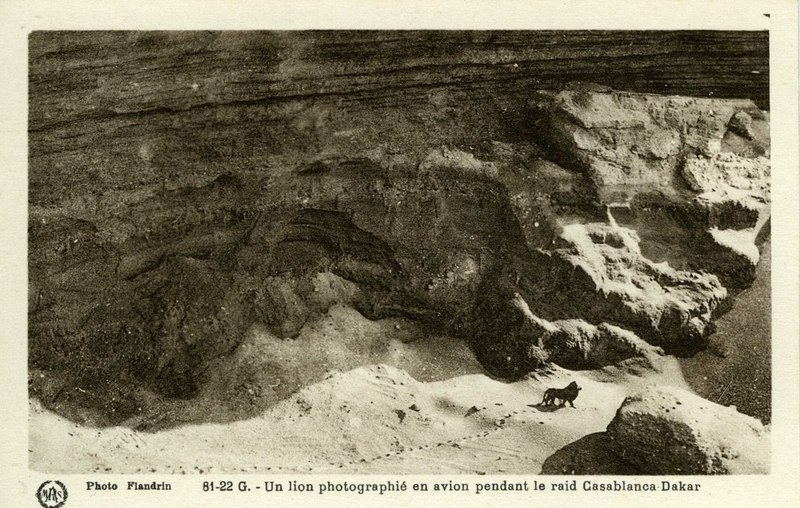

Flying from Casablanca to Dakar in 1925, French military photographer Marcelin Flandrin captured this photo in the Atlas Mountains.

It’s the last known image of a wild Barbary lion.

Flying from Casablanca to Dakar in 1925, French military photographer Marcelin Flandrin captured this photo in the Atlas Mountains.

It’s the last known image of a wild Barbary lion.

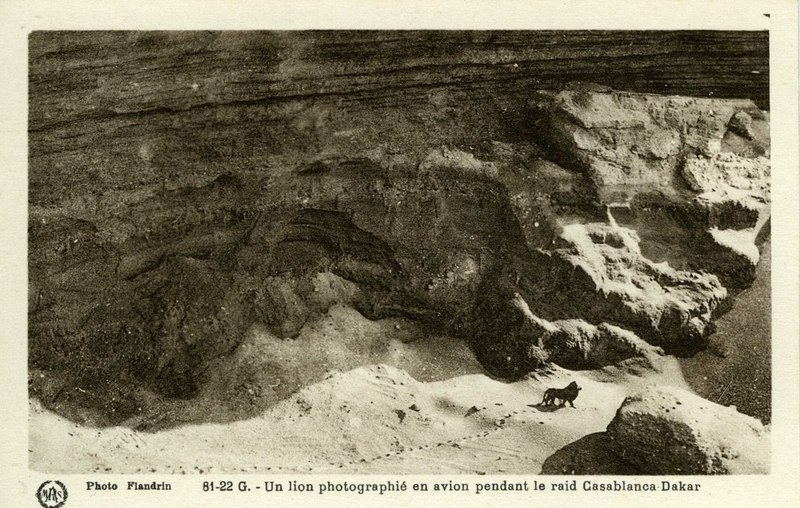

Visiting Thomas Povey in 1663, Samuel Pepys was surprised when his host opened a door to reveal an unsuspected region of the house.

At a second glance he saw that Povey had only opened a closet in which a large deceiving painting had been hung.

The painting, Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten’s View of a Corridor, still hangs at Dyrham Park today.

When [Sir Richard Francis Burton] was in India he at one time got rather tired of the daily Mess, and living with men, and he thought he should like to learn the manners, customs, and habits of monkeys, so he collected forty monkeys of all kinds of ages, races, species, and he lived with them, and he used to call them by different offices. He had his doctor, his chaplain, his secretary, his aide-de-camp, his agent, and one tiny one, a very pretty, small, silky-looking monkey, he used to call his wife, and put pearls in her ears. His great amusement was to keep a kind of refectory for them, where they all sat down on chairs at meals, and the servants waited on them, and each had its bowl and plate, with the food and drinks proper for them. He sat at the head of the table, and the pretty little monkey sat by him in a high baby’s chair, with a little bar before it. He had a little whip on the table, with which he used to keep them in order when they had bad manners, which did sometimes occur, as they frequently used to get jealous of the little monkey, and try to claw her.

That’s from Isabel Burton’s Life of Captain Sir Richard F. Burton, 1898. In her own biography of Burton, A Rage to Live, Mary S. Lovell says that Burton learned to imitate the monkeys’ sounds and believed that they understood some of them. He compiled a list of 60 words, but it was lost an 1860 fire that destroyed nearly all his papers.

The dean of a university is searching for a new chair for his chemistry department. He offers the job to one candidate, who says she’ll accept only if she can hire three new faculty members. The dean makes a commitment to support these hires.

Such arrangements are common, but that’s troubling: By making a promise, the dean has made a future act obligatory for himself, and that changes its moral status. What if the promised act would otherwise have been wrong? In this case, what if the funding for these three hires ought otherwise properly to have gone to another department?

“The fact that our moral system permits agents to dictate in this manner the moral status of their future actions seems an astonishing power to build into a moral system,” writes University of Arizona philosopher Holly M. Smith. “It is especially troubling when one notes that agents apparently can exploit promises in order to legitimize otherwise objectionable courses of action. What would we say, for example, about a moral system in which an agent may render A obligatory by simply declaring, ‘My doing A next week will be, by virtue of this declaration, morally obligatory’?”

(Holly M. Smith, “A Paradox of Promising,” Philosophical Review 106:2 [April 1997], 153-196.)

J. Van der Geer’s 2000 paper “The Art of Writing a Scientific Article” has been cited more than a thousand times, yet it doesn’t exist. Neither does the journal it appears in, the Journal of Science Communications.

The original was a “phantom reference” that had been presented only to illustrate Elsevier’s desired reference style. It seems to have been picked up by authors who didn’t understand that it was only a template, or who’d inadvertently retained the template while using it to format the rest of their references.

Anne-Wil Harzing, a professor of International Management at at Middlesex University in London, who described the confusion on her blog, concluded that the mystery “ultimately had a very simple explanation: sloppy writing and sloppy quality control.”

Manet’s painting A Bar at the Folies-Bergère is sometimes criticized for its confused composition. The bottles to the barmaid’s right stand near the back of the bar, but in the reflection behind her they stand near the front. Her own image ought to stand behind her, not off to the right. And reflection of the man she’s addressing (in the position of the painter, or the viewer) ought also to be behind her — indeed, she herself should be blocking our view of it.

But in a dissertation at the University of New South Wales, art historian Malcolm Park found that the arrangement makes sense if certain assumptions are reconsidered. The barmaid is facing the viewer across the bar, with a mirror behind her. But she’s looking diagonally along the bar, not directly across it. (See the diagram here.)

The bottles in the background and the man she appears to be addressing are both in fact to the viewer’s left, beyond the edge of the frame and so visible only as reflections. And the barmaid’s own reflection appears to our right because, from our perspective, the mirror is not directly behind her — it’s “turned” somewhat, carrying her image over to one side.

(Malcolm Park, Ambiguity and the Engagement of Spatial Illusion Within the Surface of Manet’s Paintings, dissertation, College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, 2001.)

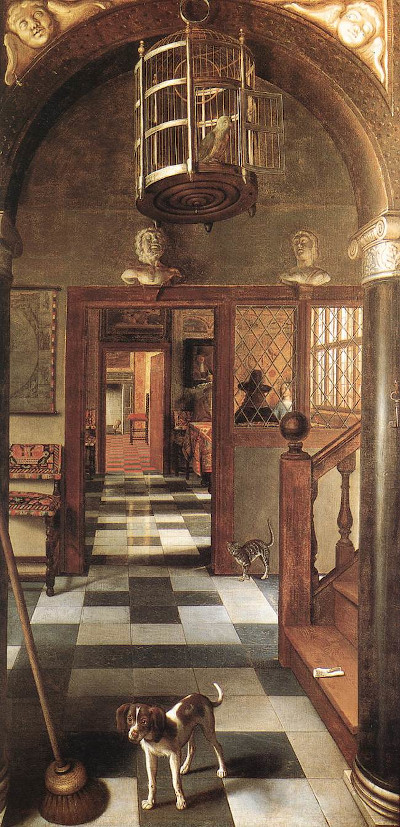

“The Pyramid,” by A.C. White, from the British Chess Magazine. White to mate in two moves.

Like many thinkers of his age, John Locke maintained a commonplace book, an intellectual scrapbook of ideas and quotations he’d found in his readings. In order to be useful, such a book needs an index, and Locke’s method is both concise (occupying only two pages) and flexible (accommodating new topics as they come up, without wasting pages in trying to anticipate them).

The index lists the letters of the alphabet, each accompanied by the five vowels. Then:

When I meet with any thing, that I think fit to put into my common-place-book, I first find a proper head. Suppose for example that the head be EPISTOLA. I look unto the index for the first letter and the following vowel which in this instance are E. i. If in the space marked E. i. there is any number that directs me to the page designed for words that begin with an E and whose first vowel after the initial letter is I, I must then write under the word Epistola in that page what I have to remark.

The result is a useful compromise: Each of the book’s pages is put to productive use without any need for an overarching plan, and the contents are kept accessible through a simple, expanding index that occupies only two pages. The whole project can grow in almost any direction, and when the pages are full then a new volume can be begun.

(Via the Public Domain Review.)

In 1833, Heinrich Scherk conjectured that every prime of odd rank (accepting 1 as prime) can be composed by adding and subtracting all the smaller primes, each taken once. For instance, 13 is the 7th prime and 13 = 1 + 2 – 3 – 5 + 7 + 11.

In 1967 J.L. Brown Jr. proved that this is true.

In 1909, Oklahoma brothers Bud and Temple Abernathy rode alone to New Mexico and back, though they were just 9 and 5 years old. In the years that followed they would become famous for cross-country trips totaling 10,000 miles. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll trace the journeys of the Abernathy brothers across a rapidly evolving nation.

We’ll also try to figure out whether we’re in Belgium or the Netherlands and puzzle over an outstretched hand.