“It has been said that love robs those who have it of their wit, and gives it to those who have none.” — Diderot

“It has been said that love robs those who have it of their wit, and gives it to those who have none.” — Diderot

In Marseille’s Salvator Hospital, the French word for “dream” seems to hang in the middle of a corridor.

It’s an anamorphic illusion — the letters are painted on the walls and ceiling to appear in perspective as an ordinary font when viewed from the correct angle.

The cat I am seen wearing as a hat in the photo, is very much alive and absolutely free. If I place her in this head-dress attitude she will remain quite still until I take her off.

— Mr. T.S. Cunningham, Chirton, Devizes, to the Strand, April 1902

A problem from the qualification round of the 2004/2005 Swedish Mathematical Contest, via the April 2009 issue of Crux Mathematicorum:

The cities A, B, C, D, and E are connected by straight roads (more than two cities may lie on the same road). The distance from A to B, and from C to D, is 3 km. The distance from B to D is 1 km, from A to C it is 5 km, from D to E it is 4 km, and finally, from A to E it is 8 km. Determine the distance from C to E.

A volunteer deals cards from an ordinary deck into two piles, stopping whenever he likes. He tosses aside one of the piles and peeks at the top card of the other pile. Then he drops the remainder of the cards on top of this pile and deals everything again into two piles. The magician, who has never touched the cards, now divines which of the two piles contains the memorized card and indeed discovers the card itself.

This trick is based on the Penelope principle, a mathematical idea worked out by Scottish magician and computer programmer Alex Elmsley. Elmsley’s technique required a perfect faro shuffle, so David Rutter revised it into a simpler version that’s entirely self-working. It was presented at the 15th Gathering for Gardner conference last year.

(Thanks, Joe.)

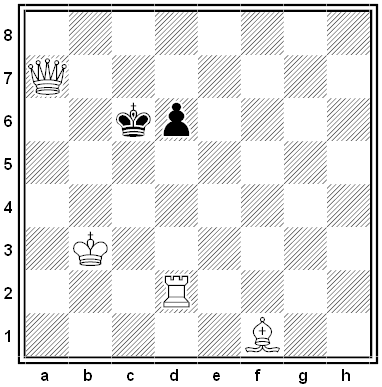

In Two-Move Chess Problems (1986), Robert Moore calls this a “very lightweight jewel.” White to mate in two moves.

In Strictly Speaking (1974), Edwin Newman points out that the names of American college presidents are strangely interchangeable: Columbia’s Nicholas Murray Butler would have projected the same impressive dignity if he’d been Nicholas Butler Murray or Butler Nicholas Murray. Kingman Brewster, president of Yale, might as well have been Brewster Kingman. Newman gives five pages of examples, drawn from the 1973 Yearbook of Higher Education:

Brage Golding, California State University

Harris L. Wofford, Jr., Bryn Mawr College

Thurston E. Manning, University of Bridgeport

Gibb Madsen, Hartnell College

Rexer Berndt, Fort Lewis College

Dumont Kenny, Temple Buell College

Woodfin P. Patterson, Jefferson Davis State Junior College

Imon E. Bruce, Southern State College

Cleveland Dennard, Washington Technical Institute

Culbreth Y. Melton, Emmanuel College

Pope A. Duncan, Georgia Southern College

Hudson T. Armerding, Wheaton College

Landrum R. Bolling, Earlham College

Mahlon A. Miller, Union College

Dero G. Downing, Western Kentucky University

Wheeler G. Merriam, Franklin Pierce College

Placidus H. Riley, St. Anselm’s College

Ferrel Heady, University of New Mexico

Lane D. Kilburn, King’s College

Hilton M. Briggs, South Dakota State University

Granville M. Sawyer, Texas Southern University

“Note also that the names are interchangeable up, down, diagonally, taking every other name, every third, fourth, fifth, and so on, at random, and — for parlor game purposes — any other way you can think of. In mixed clusters of three, especially when read or sung aloud, they are often enchanting.”

A New York Times story from 1946 observes that a man named Ole Lee, “after years of struggle,” had arranged to receive the license plate number 337-370.

“It was his name spelled upside down.”

I had my doubts, but here’s a photo.

In 1831, in the appendix to a book on the raising of trees for shipbuilding, Scottish grain merchant Patrick Matthew suggested that, over great expanses of time, “the progeny of the same parents, under great difference of circumstance, might, in several generations, even become distinct species, incapable of co-reproduction.” He’d struck on the central idea of natural selection nearly 30 years before On the Origin of Species:

As the field of existence is limited and pre-occupied, it is only the hardier, more robust, better suited to circumstance individuals, who are able to struggle forward to maturity, these inhabiting only the situations to which they have superior adaptation and greater power of occupancy than any other kind; the weaker, less circumstance-suited, being prematurely destroyed.

On learning of this, Darwin allowed that Matthew “briefly but completely anticipates the theory of Nat. Selection.” In a letter to the Gardeners’ Chronicle, in which Matthew had pointed out his early observation, Darwin wrote, “I freely acknowledge that Mr. Matthew has anticipated by many years the explanation which I have offered of the origin of species, under the name of natural selection.”

But modern observers point out that Matthew didn’t pursue the idea and may not have realized the breadth of its import. Historian of science Peter Bowler writes, “Simple priority is not enough to earn a thinker a place in the history of science: one has to develop the idea and convince others of its value to make a real contribution.” Darwin called Matthew’s note “a complete but not developed anticipation … Anyhow one may be excused in not having discovered the fact in a work on Naval Timber.”

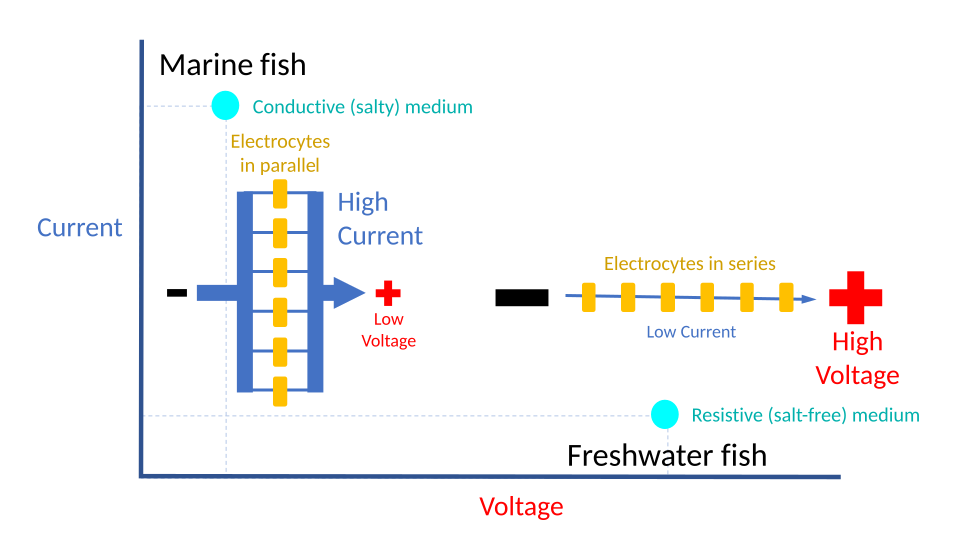

Among electric fish, those that live in freshwater have their generating cells arranged “in series”; in saltwater they appear “in parallel.”

Seawater conducts better than fresh water, so freshwater fish need to generate a high voltage to overcome the resistance of their medium. Their electricity-producing cells are arranged in series.

Marine fish operate at higher currents but lower voltages, so their electrocytes appear in parallel.