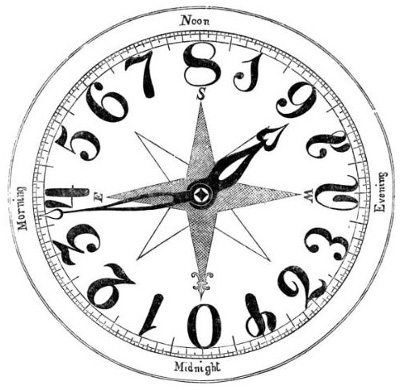

In 1859, far ahead of its application in computing, engineer John W. Nystrom proposed that we adopt base 16 for arithmetic, timekeeping, weights and measures, coinage, and even music.

“It is evident that 12 is a better number than 10 or 100 as a base, but it admits of only one more binary division than 10, and would, therefore, not come up to the general requirement,” he wrote. “The number 16 admits binary division to an infinite extent, and would, therefore, be the most suitable number as a base for arithmetic, weight, measure, and coins.”

He named the 16 digits an, de, ti, go, su, by, ra, me, ni, ko, hu, vy, la, po, fy, and ton, and invented new numerals for the upper values. Numbers above this range would be named using these roots, so 17 in decimal would be tonan (“16 plus 1”) in Nystrom’s system. And he devised some wonderfully euphonious names for the higher powers:

| Base 16 Number | Tonal Name | Base 10 Equivalent |

| 10 | ton | 16 |

| 100 | san | 256 |

| 1000 | mill | 4,096 |

| 1,0000 | bong | 65,536 |

| 10,0000 | tonbong | 1,048,576 |

| 100,0000 | sanbong | 16,777,216 |

| 1000,0000 | millbong | 268,435,456 |

| 1,0000,0000 | tam | 4,294,967,296 |

| 1,0000,0000,0000 | song | 1612 |

| 1,0000,0000,0000,0000 | tran | 1616 |

| 1,0000,0000,0000,0000,0000 | bongtran | 1620 |

So the hexadecimal number 1510,0000 would be mill-susanton-bong.

The system was never widely adopted, but Nystrom was confident in its rationality. “I know I have nature on my side,” he wrote. “If I do not succeed to impress upon you its utility and great importance to mankind, it will reflect that much less credit upon our generation, upon scientific men and philosophers.”