Author: Greg Ross

Insight

We can’t control external events, but we can control our response to them. So, the Stoics taught, it’s wise to accept a fate that we can’t change. Zeno and Chrysippus summed this up in a parable:

When a dog is tied to a cart, if it wants to follow, it is pulled and follows, making its spontaneous act coincide with necessity. But if the dog does not follow, it will be compelled in any case. So it is with men too: even if they don’t want to, they will be compelled to follow what is destined.

Cleanthes expressed this in a prayer:

Lead me, Zeus, and you too, Destiny,

To wherever your decrees have assigned me.

I follow readily, but if I choose not,

Wretched though I am, I must follow still.

Fate guides the willing, but drags the unwilling.

Succinct

Travelling to England with his wife and daughter in the Norwegian freighter Halibut, which ran into rough seas, [Sir Robert Menzies] sent this cable to relatives:

At sea off Perth: Exodus X, 23.

In the Bible they found these words:

They saw not one another, neither rose any from his place for three days.

— Ray Robinson, ed., The Wit of Sir Robert Menzies, 1966

Viewpoints

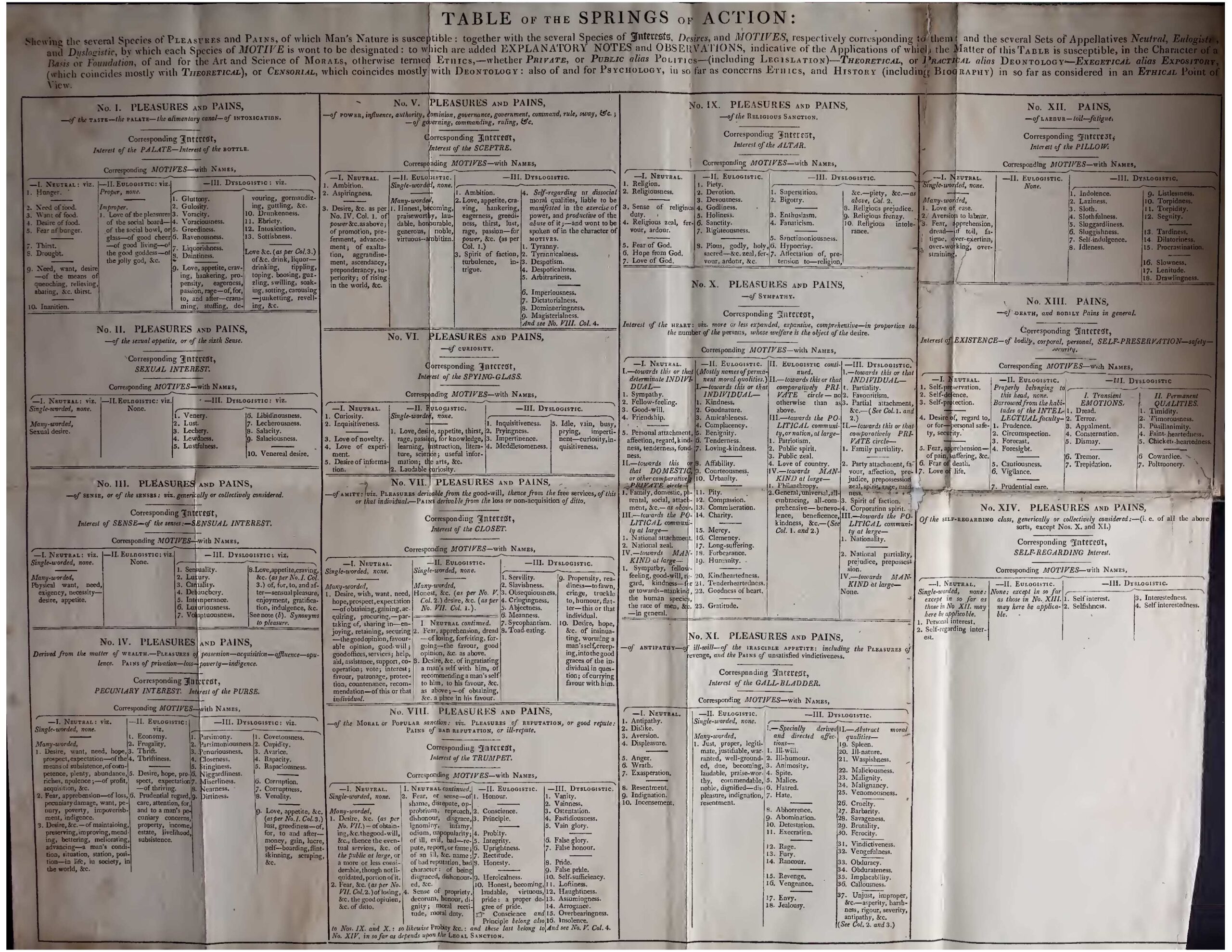

Jeremy Bentham made a table of the springs of action, where every human desire was named in three parallel columns, according as men wish to praise it, to blame it, or to treat it neutrally. Thus we find in one column ‘gluttony,’ and opposite it, in the next column, ‘love of the pleasures of the social board.’ And again, we find in the column giving eulogistic names to impulses, ‘public spirit,’ and opposite to it, in the next column, we find ‘spite.’ I recommend anybody who wishes to think clearly on any ethical topic to imitate Bentham in this particular, and after accustoming himself to the fact that almost every word conveying blame has a synonym conveying praise, to acquire a habit of using words that convey neither praise nor blame.

— Bertrand Russell, Marriage and Morals, 1929

Bentham had published the table in 1817. “By habit,” he wrote, “wherever a man sees a name, he is led to figure to himself a corresponding object, of the reality of which the name is accepted by him, as it were of course, in the character of a certificate. From this delusion, endless is the confusion, the error, the dissension, the hostility, that has been derived.”

Family Matters

The humorous will of Dr. Dunlop of Upper Canada is worth recording, though there is a spice of malice in every bequest it contains.

To his five sisters he left the following bequests:

‘To my eldest sister Joan, my five-acre field, to console her for being married to a man she is obliged to henpeck.

‘To my second sister Sally, the cottage that stands beyond the said field with its garden, because as no one is likely to marry her it will be large enough to lodge her.

‘To my third sister Kate, the family Bible, recommending her to learn as much of its spirit as she already knows of its letter, that she may become a better Christian.

‘To my fourth sister Mary, my grandmother’s silver snuff-box, that she may not be ashamed to take snuff before company.

‘To my fifth sister, Lydia, my silver drinking-cup, for reasons known to herself.

‘To my brother Ben, my books, that he may learn to read with them.

‘To my brother James, my big silver watch, that he may know the hour at which men ought to rise from their beds.

‘To my brother-in-law Jack, a punch-bowl, because he will do credit to it.

‘To my brother-in-law Christopher, my best pipe, out of gratitude that he married my sister Maggie whom no man of taste would have taken.

‘To my friend John Caddell, a silver teapot, that, being afflicted with a slatternly wife, he may therefrom drink tea to his comfort.’

While ‘old John’s’ eldest son was made legatee of a silver tankard, which the testator objected to leave to old John himself, lest he should commit the sacrilege of melting it down to make temperance medals.

— Virgil M. Harris, Ancient, Curious, and Famous Wills, 1911

Sibling Rivalry

The peculiar circumstances of life aboard the International Space Station both advanced and retarded astronaut Scott Kelly’s age relative to that of his identical twin brother Mark, who remained on the ground.

Radiation, weightlessness, and changes in diet shortened Scott’s telomeres more quickly than his brother’s, effectively causing him to age more quickly.

At the same time, due to relativistic effects, Scott aged about 8.6 milliseconds less than Mark during his year in space.

Illumination

The Tyrians having been much weakened by long wars with the Persians, their slaves rose in a body, slew their masters and their children, took possession of their property, and married their wives. The slaves, having thus obtained everything, consulted about the choice of a king, and agreed that he who should first discern the sun rise should be king. One of them, being more merciful than the rest, had in the general massacre spared his master, Straton, and his son, whom he hid in a cave; and to his old master he now resorted for advice as to this competition.

Straton advised his slave that when others looked to the east he should look toward the west. Accordingly, when the rebel tribe had all assembled in the fields, and every man’s eyes were fixed upon the east, Straton’s slave, turning his back upon the rest, looked only westward. He was scoffed at by every one for his absurdity, but immediately he espied the sunbeams upon the high towers and chimneys in the city, and, announcing the discovery, claimed the crown as his reward.

— Charles Carroll Bombaugh, Gleanings From the Harvest-Fields of Literature, 1869

To the Life

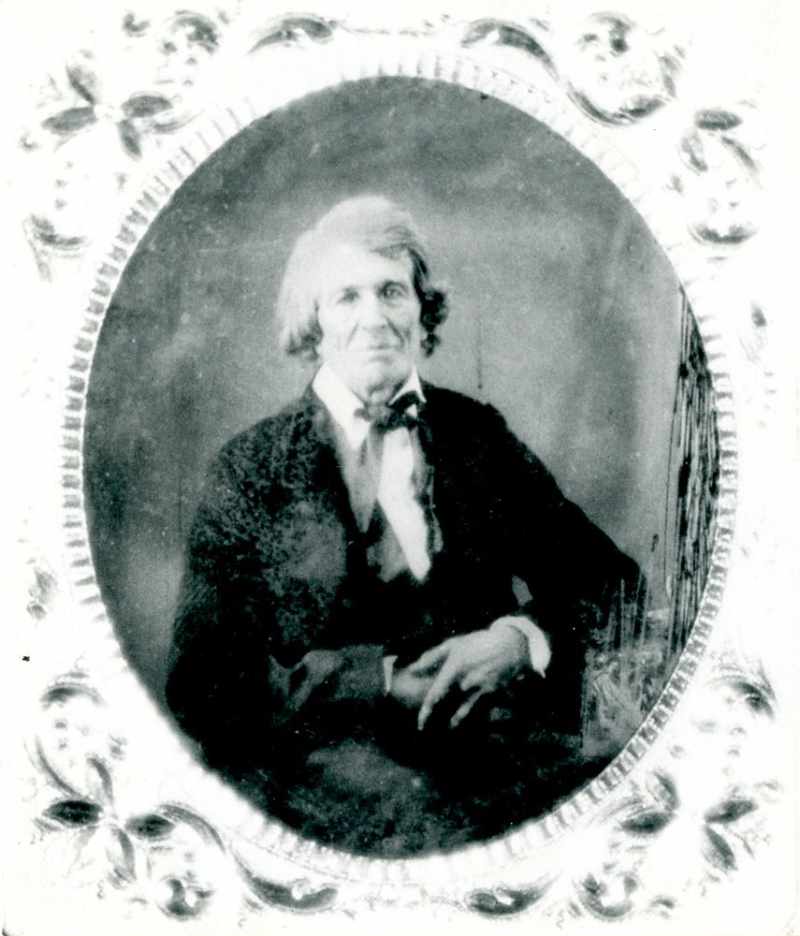

John Owen, one of the last veterans of the French and Indian War, lived to be 107 and posed for this photograph shortly before his death in 1843.

That makes him one of the earliest-born humans ever to be photographed. He was born in 1735.

Busywork

What’s the sum of all the digits used in writing out all the numbers from one to a billion?

Unquote

“I always feel an optimist when I emerge from a tunnel.” — Robert Lynd