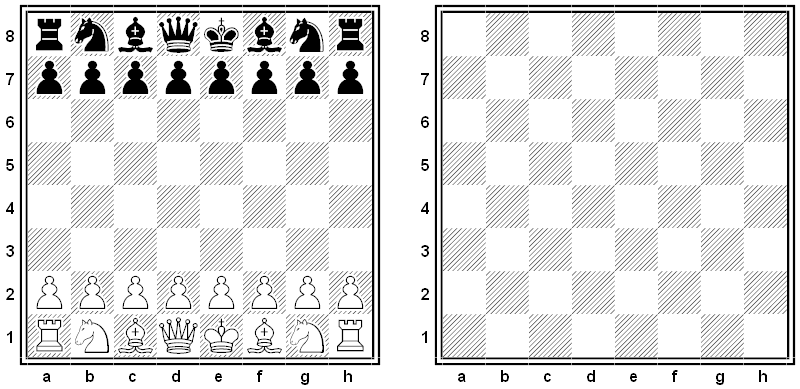

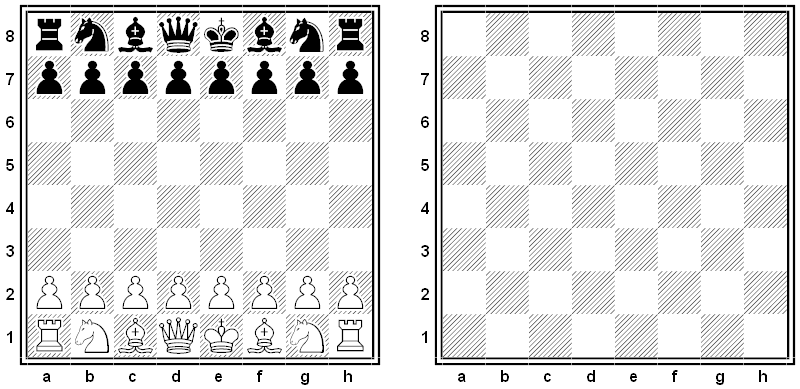

English chess enthusiast V.R. Parton invented this variant in 1953. The game is played on two boards, starting with the normal opening position on one board and a second board empty. The trick is that a piece that completes its move on one board “vanishes strangely off its board to appear suddenly on the other board, magically out of thin air!”

There are two stipulations: A move must be legal on the board on which it’s played, and the square to which the piece is transferred on the opposite board must be vacant. (This means that a piece can make a capture only on the board on which it stands.)

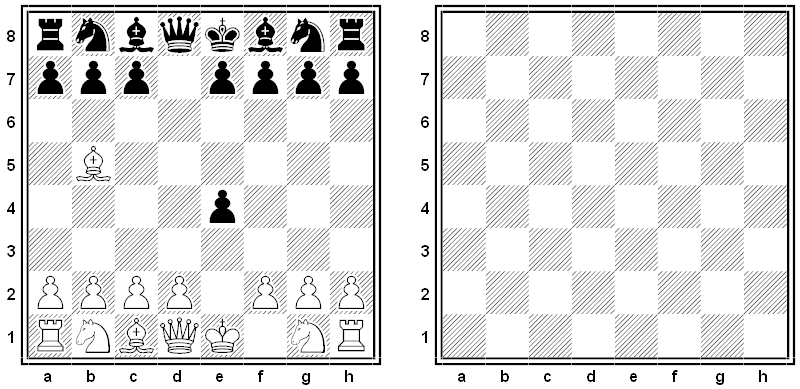

This makes things very confusing. Here’s a simple three-move game. White plays 1. e4, which means that his king pawn advances from e2, passes “through the looking glass,” and arrives at e4 on the second board. Black responds with 1. … d5, so his queen pawn arrives at d5 on the second board. White plays 2. Be2, meaning that his king’s bishop is transferred to e2 on the second board. And now Black makes the mistake of playing 2. … dxe4 — his pawn on d5 on the second board captures the white pawn there, which means the white pawn is removed from play and the black pawn finds itself on e4 on the first board. That’s a mistake, because White can play 3. Bb5:

The white bishop returns to the first board, checking the black king. Strangely, this is checkmate: Black can’t capture the attacking piece or move out of danger, and he can’t interpose a piece — any piece that he moves on the first board will find itself on the second, and there are no pieces on the second board that could move to c6 or d7.

Parton wrote, “One board being as a looking-glass to the other, the resulting play is a game which has a character as fantastic perhaps as Alice’s own game in Through the Looking-Glass.”

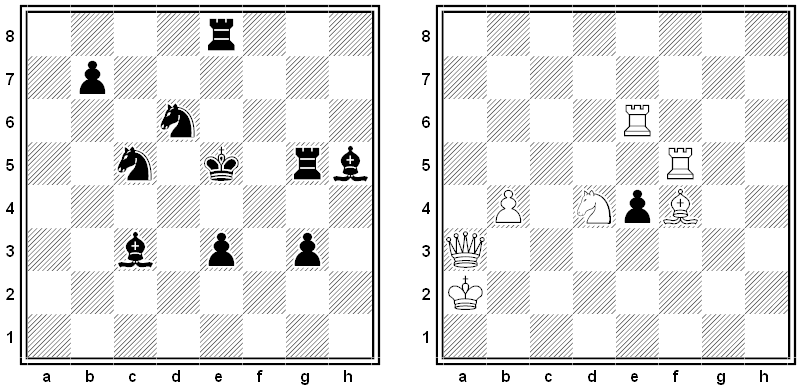

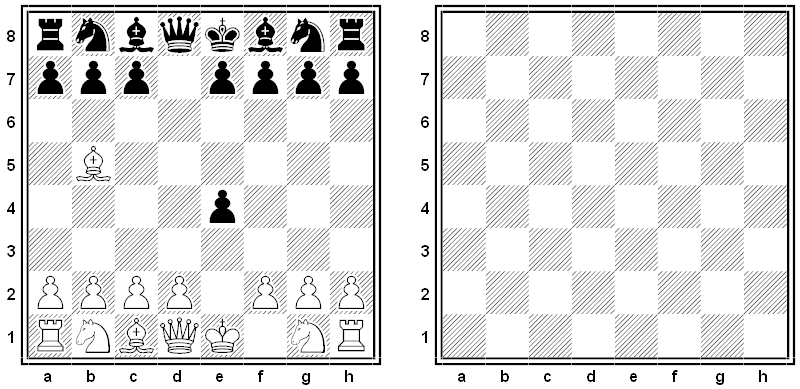

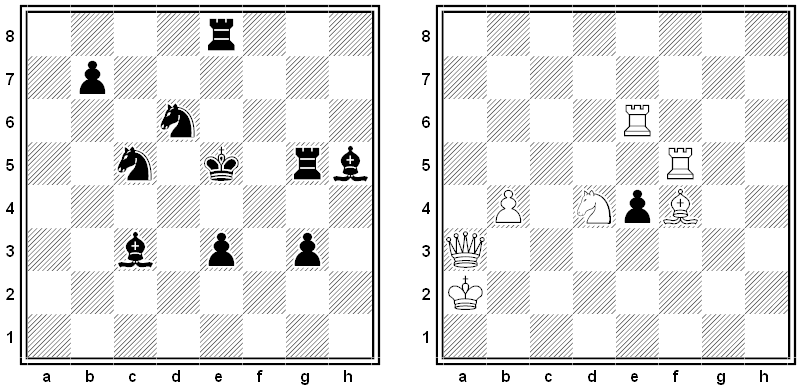

Here’s an Alice chess problem by Udo Marks. How can White mate in two moves?

|

SelectClick for Answer |

Remarkably, White wins with a simple waiting move, 1. Kb1, returning his king to the first board where it’s out of harm’s way. Now any move that Black makes exposes him to some inescapable danger. For example, if he moves his b-pawn then White can move his knight to c6 on the first board, checking Black’s king. There is no safe vacant square on the second board to which the king might move, so the game is over. Black has 44 available moves, but all lead to checkmate.

|